Medardo Rosso, Sculptor of Light

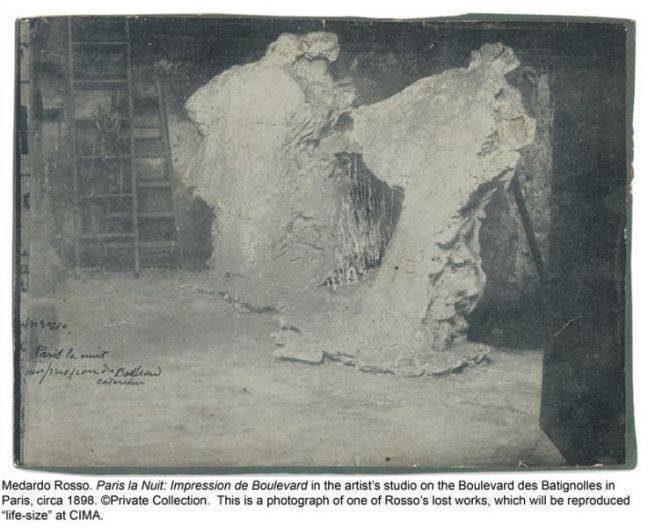

Medardo Rosso is the star of the second annual show at CIMA, the Center for Italian Modern Art. On display in this comprehensive and carefully curated retrospective are not only his bronze, marble and wax sculptures but also original photographs, prints and drawings.

“The hope of the show is to encourage studies of the artist by raising questions and ideas that

will spark discussion and flesh out his themes with a new, fresh eye,” says Laura Mattioli, welcoming us into the kitchen of CIMA’s luminous Soho loft for an espresso.

She and Danila stroll among sculptures that seem to be watching us and photographs of Medardo Rosso redolent of a bygone era. Danila Marsule Rosso, Medardo Rosso’s great-granddaughter, explains his “uncomfortable” role in the family and his unique personality, re-telling stories she heard from her grandparents.

Ms. Rosso, would you tell us how are your great-granfather and his work remembered in your family?

Medardo Rosso began his artistic career in Milan and undertook the bohemian life at the end of the 1800s.

He was always a rebel, but he was talented too. He was very good at drawing and won awards at school for penmanship, given his great technical skill. Then he left the family to go to Paris, having understood that if he stayed in Milan he would never evolve and achieve the success he desired.

He had a lot of problems when he arrived in France. He had no money and even wound up in the hospital because he was dying of hunger and cold. He lived in a basement apartment… until he managed to get his own studio after his work began to garner recognition and admiration. As my grandmother tells it, Medardo was a very difficult, peculiar personality: he kept odd hours and came back home at all hours.

He’d give my grandmother dolls then take them away. Francesco, the youngest son, was put to work immediately to make up for his father’s absence… in short, he’s someone the family holds at arm’s length.

You are the proprietor of the Medardo Rosso Museum in Barzio and the family archive. When did you begin this business?

In the 1990s, when my grandmother died. I began taking a personal interest in the Medardo Rosso archive, studying the documents, reestablishing contacts, and creating order out of the chaos that had been created. The result was to give logical and philological sense to Medardo’s body of work—the letters, writings and photographs.

The Museo Rosso then helped sponsor the 2009 publication of Medardo Rosso. Catalogo Ragionato della scultura, published by Skira Editore. Rosso achieved great success and his innovative style won him many imitators. And that meant people were interested in him. We organized exhibits in Europe: of his photography in Berlin in 2006, in Venice in 2007, and at the Boijmans Museum in Rotterdam in February 2014. (Smiling) Now we have finally reached his beloved New York, and CIMA seemed to me to be the best space in which to introduce Americans to Medardo Rosso.

Ms. Mattioli, what is the connection between the artist and New York?

Besides being known in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s, Medardo Rosso was also known in New York. He had a show at MOMA, and for him it was like his consecration. Margaret Scolari Barri, the art historian and founding director of MOMA, wrote exceptional essays on Medardo Rosso. But the attention he aroused in the U.S. dwindled over time.

There were few public exhibits after that period, and critical studies have changed a lot since then. They have focused on other subjects, like photography. Medardo Rosso was aware that he was doing work that no one in his lifetime could understand. He was doing experimental work, re-photographing the same prints again and again, changing the exposure, increasing the contrasts to make them more evanescent. We have curated an exhibit that fully reflects his artistic and thematic transformations via the lens of photography, sculpture and drawing. For those who have yet to see the retrospective, the show will be up until June 27.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.