Elena Ferrante. Italy’s Best-selling and Most Secretive Author

Her popularity is as extraordinary as is her secrecy. Neapolitan author Elena Ferrante’s novels in translation have won lavish praise throughout the English-speaking world, from The New York Times to Entertainment Weekly, The Independent, Slate, and on, and on.

Admired Abroad

For the Boston Globe, “Everyone should read anything that has her name on it.” For the Daily

Beast, she is one of the world’s most talented writers.

For The Guardian, “Nothing like this has ever been published before.” And for the London Economist, she writes with “crystal prose.” Others throw around words like “utterly brilliant” and “talented,” while tours of the places in her native Naples described in her books are now the latest chic in Neapolitan tourism.

Elena Ferrante’s quartet of books (see above) are known in English as the Neapolitan Novels, published in English by Europa Editions of New York and, in the original Italian, by what is in Italy a minor publisher, E/O.

The Stories

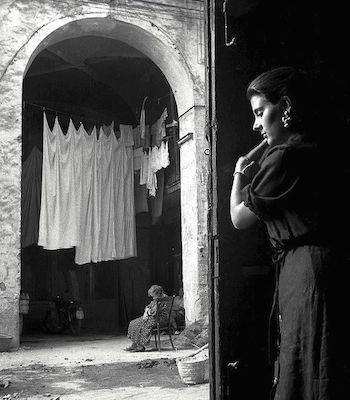

The stories begin in the Fifties, in the poverty-stricken quartieri malfamati (infamous neighborhoods) of Naples, where violence and crime are the order of the day. As the boom years

begin, the chorus of protagonists headed by Lila and Elena—narrator and name-sake of the author—are seeking to leave behind the misery of their childhood. They want marriage and money, success and happiness: can it happen?

From the time they were young children Elena and Lila are loving friends, but also tough competitors with, ever in the background, the broader social and class conflict of their time and place. In the end, the frustrated, intelligent Lila’s schooling ends with fifth grade, and she is married as a teenager and has children when herself scarcely more than a child. She never leaves the slum where she was born, but, thanks to her keen mind, forges ahead brilliantly. By contrast, Elena graduates from the prestigious Scuola Normale University at Pisa, then enjoys a comfy existence in Florence with her leftist husband and two children, only to turn her back on that life for an old love, and return home, where she eventually takes on the local organized crime bands of the Camorra.

The Ferrante Enigma

Italian readers are almost if not quite as enthusiastic as the English speakers.

This month “Silvia” wrote, “One fact struck me, when I was just 50 pages from the end. In four books I could not yet figure out which of the two women is the protagonist. Perhaps this shows how clever the author is (who seems to be a woman). Sometimes it is Lina, sometimes, Elena... a very sad character, despite her existence in a modern world, her sometimes exaggerated feminism, and despite her desire to attack the backwardness of the South. It is as if, having everything, something is still missing.”

Reader “Carla” called the quartet one of the best reads in recent years. “Elena Ferrante involved me in her story as hadn’t happened to me in a long time, and the last book is so touching. Bravissima, whoever you are.” The words “whoever you are” are crucial, as are Silvia’s “seems to be a woman.” The name Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym, and the author has chosen to keep his/her identity an enigma. For whatever reason, Ferrante is never photographed, never interviewed in person, but solely and occasionally by email.

That pen name provides a hint of her literary genesis, which seems a reflection of the name of Elsa Morante (1912 - 1985), the famous postwar author and for many years the wife of fellow novelist Alberto Moravia. The author of La Storia (published in English as History), Morante was half Jewish, and wrote that book, now a classic, as a result of having to hide from the Nazis for a year during WWII. Curiously, Ferrante’s first novel, L’Amore Molesto (Nasty Love) published in 1992, won the Procida Isola di Arturo - Elsa Morante prize

Controversial in Italy

Not all Italians delight in Ferrante’s work. When fellow Neapolitan Roberto Saviano nominated Ferrante for the prestigious literary award, the Premio Strega, last February, Massimiliano Parente wrote somewhat snidely in Il Giornale that first Ferrante declined, but then accepted out of “respect” for Saviano and his work, as Ferrante wrote Saviano. “Ferrante is a bestseller author of weepy meatloafs,” said Parente, “who constructed the personality of the invisible author, one more form of exhibitionism.”

The brilliant (and eccentric) author Aldo Busi, writing in Dagospia, called Saviano’s nomination of Ferrante ridiculous and Ferrante guilty of writing a “family-ish broth of Parthenopean sentimentalism” which gave him a “lightning attack of psychic diabetes.”

Such acidity did not go unnoticed: the daily Il Fatto Quotidiano called Busi’s hostility gratuitous and other critics agreed, saying that, while Ferrante wrote of sentiment, she was not sentimentalist and that the reactions of “a certain part of the Italian literary world are so vehement as to be ridiculous.”

For literary critic Giuseppina Dota of Foggia, for the past two decades, “the unanimous judgement has always been that Ferrante writes magnificently.”

In the event, Ferrante came in third in the Strega Prize competition, with 59 votes; the winner was Nicola Lagioia with 145 votes for his novel La Ferocia, published by Einaudi.

Anonymity or Timidity?

Still, many continue to ask if “Elena Ferrante” is actually male or female. Why should an author dodge publicity, unless this is, in itself, a publicity ploy? One theory is that she is Anita Raja, who works for the publisher E/O and is the wife of the writer Domenico Starnone, 72, and a Neapolitan. For some, Starnone and Raja are together the Ferrante writing team, which both vehemently deny.

Speaking for herself, in an interview for the Paris Review Ferrante explained that she had chosen anonymity in the Nineties because, “I was frightened by the possibility of having to come out of my shell. My timidity prevailed, then there was the hositility of the media, which paid no attention to my books. It wasn’t the book that counted, for them, but the author’s aura.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.