The President vs. the Magistrates

ROME - The ongoing dispute that pits a courageous magistrate in Palermo against the much admired and admirable President of Italy, Giorgio Napolitano, is one of the saddest Italian stories ever told. For that matter, it is also hard to tell.

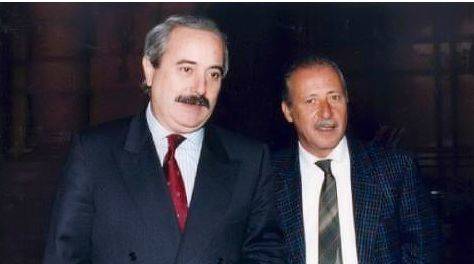

The story begins with a sub rosa negotiation in 1992 between top Mafia bosses and representatives of the Italian state, purportedly including high military officers. Although some still question whether the negotiation took place at all, an Italian court is on record affirming that it did. As a result, many here are asking tough questions: was such a negotiation legal, who did it, in exchange for what, what were its consequences? Was this negotiation related to the Mafia murders of magistrate Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, and, if so, how?

From Palermo, prosecutor Antonio Ingroia is fighting to have those responsible for what he considers an illegal negotiation brought to trial. Most unfortunately for all concerned, the phone taps he ordered as part of his inquiry led straight into the Quirinal Palace (the Italian White House), where Nicola Mancino, one of a dozen men under investigation, was overheard appealing for help in dodging involvement in the Palermo inquiry. Although no one knows what was said, in two phone taps the President himself is heard speaking to Mancino. A former Senate president, Mancino was Interior Minister during the presumed negotiation. In a phone tap already in the public domain Mancino seems to express fears of being indicted for false testimony in a previous trial.

That the conversations took place is certain, but what was said between Napolitano and Mancini is unknown, and probably never will be. The Quirinal Palace takes the view that the Italian constitution prohibits the tapping of Presidential telephone conversations. Since not everyone agrees on this, Napolitano himself asked the Constitutional Court (the Italian supreme court) to rule upon the legitimacy of the phone taps, on grounds that to allow them as trial evidence would create a precedent. This reduces the issue, as Professor Maurizio Viroli of Princeton University has put it, to the Court being asked to choose between declaring the head of state "untouchable" or abandoning the prosecutors in Palermo. Few believe the Court will find against the President.

Assuming that the negotiations actually took place, their apologists say that the decision to block Mafia mass murders and terrorist-style bombings of tourist sites gained time for the state to bring the Mafia to heel. The counter-arguments are, first, that the state took the exact opposite high moral ground when it refused to negotiate with the Red Brigades in order to save the life of Aldo Moro: what exactly was the difference? Secondly, the Mafia was not at all brought to heel--on the contrary, the work of all those who contributed to the success of the maxi-trial in Palermo was squandered when hundreds of convicted mafiosi were, apparently thanks to the alleged negotiations, released well ahead of time. Third, the Mafia seems to have been given carte blanche to go on with its newly precision-style murder campaign, with the resulting deaths of the inquiring magistrate Giovanni Falcone and prosecutor Paolo Borsellino.

Among those in Ingroia's investigation are politician Marcello dell'Utri, who spearheaded creation of the formidable Sicilian branch of Silvio Berlusconi's Partito della Liberta' (PdL) in 1992. Speaking for that party, one of its top leaders, Fabrizio Cicchitto, a former member of the clandestine P2 Masonic Lodge, criticized Ingroia for "violation of all the laws." An editorial in Giuliano Ferrara's rightist Il Foglio went further, in particularly shrill language. "The political puppet firecracker [Ingroia], who has been passed off as an anti-Mafia icon but unmasked, goes on aiming ever higher. Now he wants either to get rid of or to invalidate the head of state. He's a Taliban....with methods worthy of the Spanish Inquisition."

However, it is obvious that some of those leaping to the defense of Presidential prerogatives are using the conflict as a convenient way to curtail other Palermo investigations into the Mafia. As Ingroia himself said this week, "To reduce this to a clash between the Palermo Prosecutors and the Quirinal, and moreover [between me and] the President of the Republic, is distressing and essentially false.... It is obvious that the legitimate conflict of attribution raised by the Quirinal has been exploited to attack the Palermo prosecutors."

In his editorial Ferrara added that the very officials under investigation, who include military officers, were precisely those who "successfully penetrated the criminal organization of Cosa Nostra, and virtually destroyed it." This is more than debatable. The military wing of Cosa Nostra lost its cutting edge, money and world power as a result of the pressure put on it by the Sicilian magistracy in the 1980s with the help of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, as this reporter can testify.

In a broader sense, the Mafia depended upon Big Heroin from Southwest Asia, but were undercut in the Nineties by the cocaine traders of Latin America; by the Calabrian 'Ndrangheta working with the Russians; by the Camorra in Naples working with Chinese shipping importers; by manufacturers worldwide of synthetic drugs and others still. The Sicilian Mafia reverted successfully back to the door-to-door protection racket and to improving its connections in the North of Italy.

Even were this true, even if the Sicilian Mafia were substantially reduced in power, Italy owes it to Falcone and Borsellino that the full story behind their murders be investigated and known, and prosecutor Ingroia's work allowed to continue with robust support. For, as the subsequently martyred Judge Falcone once said, "To be left alone is to die." For the moment, the plan is for Ingroia to be shipped to a UN post in Latin America.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.