Sergio Romano: Populism, Panic and Opportunity

Trump: Europe’s Reactions

Ambassador, would you describe for our American readers Europe’s reaction to Trump’s election? Did the outcome come as a surprise to Europe too? Europeans follow the American press, so they had the impression that Hillary Clinton’s victory was a foregone conclusion. We got it wrong, but our mistake was based on projections from the United States.

I think the reactions in Europe take two forms. First, Europeans are wondering how it will affect their relationship with the United States. That is a legitimate question. I’d almost call it an inevitable one. The second worry is rather irrational, though in certain respects it too is justified. I’m referring to the election of Trump somehow bene ting populist movements in Europe. Why should it? I don’t think there’s necessarily a connection between them, though it is a fact that the populist movements in Europe have hailed Trump’s victory as if it boosted their own cause.

Do you think in Europe the fear is being kept covert? I mean, might those afraid of Trump have tended to reinforce—more or less unconsciously—their hope that Clinton would win with some sort of wishful thinking?

Honestly, a lot of analysts knew Hillary Clinton was a pretty weak candidate, or at the very least a vulnerable one. She belongs to the establishment and without a doubt American society, like all western societies right now, is tired if not sick of the establishment. In addition, Europeans didn’t quite get this email business, but they did get the impression Clinton was hiding something, and therefore everyone wondered how that would in uence the American vote. The fact is that Hillary Clinton won the majority of the popular vote, so you can’t say things went all that badly. Sure, she lost the electoral vote, calculated geographically, which is fundamental to a federation. Maybe that’s another thing Europeans haven’t quite understood. The mechanism and especially the “philosophy” of the Electoral College typical of federations appear to be little comprehended in Europe.

Populism: Europe/America, Le /Right

You alluded to the effect of “populist” European movements. Europe appears to have fallen into a crisis in part due to the effect of these movements often associated with the same phenomenon that Trump embodies in the US: a populist reaction to the negative effects of globalization. Can you help us sort these concepts out?

The negative repercussions of globalization have clearly in uenced the voting results in both the US and Europe. From that standpoint the two phenomena are fairly comparable. But I think the motives driving European discontent differ. The Euro and the European Union are at a difficult stage. The US has no such problem. But Trump’s win was strategically used by populist European leaders to place everyone in the same basket and present the American tycoon’s win as an indication of their imminent triumph.

In the US there is also movement on the side opposed to Trump, a desire to counter Trump’s rightwing populist rhetoric with leftwing populist rhetoric, especially regarding immigration. Could you help clarify that situation for us too?

The problem of illegal immigration in America and the problem in Europe are different in kind. The United States has a problem with Latin America in particular, and the Mexican border is de nitely one of the major hot spots. But that concerns a socio-economic type of immigration: immigrants who, unlike those in Europe, are not politically motivated. They’re not escaping extreme political situations triggered by wars, for example. We don’t know how many of our immigrants come over for social and economic reasons, but there is no question that they fit a much more shocking humanitarian prole. These ships crossing the Mediterranean that we absolutely must save!

In Europe we have yet to decide how to solve the problem, in part because, unlike the United States, we have no representative mediators. The US can always talk to the governments of Mexico or Costa Rica or Honduras. Those are states with which you can make a deal. Who is there for us to talk to? A large number of our immigrants come from Libya, where we do not have mediators. We might look to send them back to their country of origin, but what country would that be? We’d risk being culpable of crimes against humanity.

There may also be another difference, one not always mentioned. Immigration, illegal or not, has become part of the economic fabric of the country. Many work as waiters, laborers, housekeepers and drivers for the wealthy. Their kids go to school. In some states young immigrants can obtain a driving license. They marry and their children become American. Recently New York City created an ID that can be used by people who are here without permission. The mayor has refused to provide registries to the federal government. So the situation in this country is truly diverse, and I wonder if people in Europe are aware of that.

I don’t think so. That is yet another difference. It needs to be better understood.

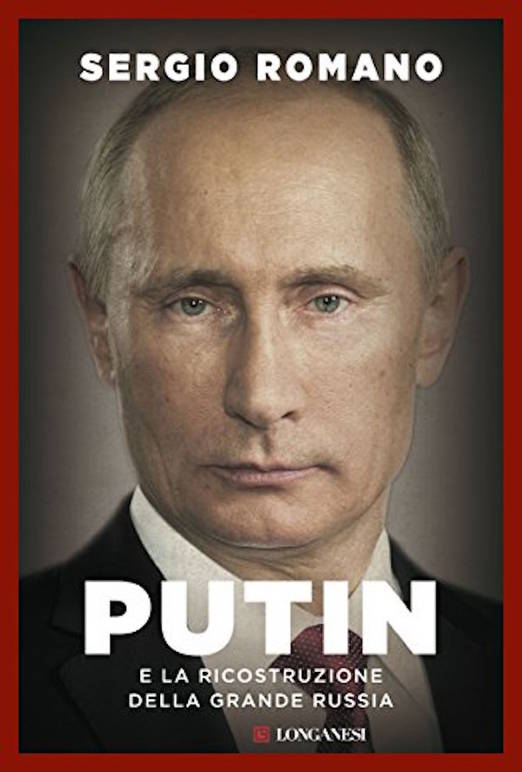

Putin and the Great Russia

You have a new book out, Putin and the Reconstruction of Great Russia, in which you talk about the rise of the Russian president. Could you tell us more?

First and foremost I tried to explain Putin’s motives. He belongs to an institution—the KGB—that continues to play, an important role in domestic politics. I don’t think Putin was ever a strict communist of an ideological bent but instead someone branded by his association with a very particular organization. No doubt it was the military arm of a repressive government. But it is also an organization where one learns a lot. They view the world with a certain realism and know perfectly well what their country’s aws are. So they have always played a secret, mysterious role, one of real malice, but also in certain ways an instructive role. And I think that kind of describes Putin. He entered politics after his negative experience in Dresden, where he had the impression that the Russian state was falling apart. To him that was humiliating, painful. It’s no surprise he dedicated his political life to restoring Russian authority. That’s his goal and he pursues it by the means at his disposal. I don’t think western democracies sufficiently appreciate that.

Just as they didn’t understand that NATO, having expanded the way it did, could not have been seen by Moscow as anything but a threat. NATO isn’t just any historic alliance. It’s an alliance designed to make war with an enemy which lies identi ably beyond what used to be called the iron curtain. If Moscow sees NATO expanding to the east, it’s going to draw certain conclusions. The West didn’t understand that Ukraine could have been important for Europe had it remained neutral. Instead, by backing the—minor, in my opinion—part of Ukraine that wanted to definitely break with Russia, they ended up turning Ukraine into a contested country. And we all know how that turned out.

The book also tries to explain how Putin can be quite useful for European and American policy and for western democracies in general.The Islamic problem, for example: we think it is our problem exclusively, but the Russians have had to deal with it in ways that are, in a certain light, more dramatic. Just look at the perils of radical Islam in Chechnya, from the Beslan school siege to the occupation of the theater in Moscow. We merely said, “It was all staged by the KGB.” Those claims hold no water and are beside the point. So I try to explain where we went wrong.

Putin, the US and Europe

Getting back to Trump, will the new president change the relationship between the United States and Russia? Is it too soon to tell?

Claims about Putin’s eagerness to see Trump win are unjustified. Russians, like the Soviets before them, have always preferred Republicans to Democrats. Based on their experience, they have always had more constructive, less ideological relations with Republican presidents. (Take Reagan and Nixon, for example.) Democratic presidents risk being ideological, as if they felt invested with a missionary mandate, something that all Russian leaders—and not only Putin—can’t stand. The same repressive policies of Putin in the face of Russia’s civil society—bans on protests, arrests, police violence—things anyone who knows and loves the country cannot learn of without great dismay—can be partially explained in this way. I’m not justifying it, but it does explain how Russians like Putin see the hallmarks of the west and the United States in these protests, countries that finance non-governing organizations and whose democratic humanitarian character is fundamentally hostile to the regime. These things should not stop us from trying to make Russia a more democratic country, but we must be aware of them—otherwise we risk taking the wrong course of action.

In your opinion, could Trump’s “isolationist” policies, if acted upon, have a negative effect on Europe?

If Trump really does take the hard line he has proposed and tells Europe it has to pay for its own defense—to me that seems like an opportunity to seize! If the US president has no interest in defending us, then it’s up to us. Federica Mogherini, the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, is taking the right course of action in pursuing a four-way effort between Spain, France, Germany and Italy to re-launch a European defense policy. If American policy is really going to be, shall we say, isolationist (to give it a label) that could be an opportunity for us.

A Lesson in Clarity

On a more personal note, how do you combine recounting history with such detail and specifity and your effortless narrative style? How would you explain it to a student?

[Laughs.] My answer is banal but it’s the only one I’m able to tell myself. When I started writing—like a lot of kids who like to write,

I started early—I would give my father what I wrote, essays and stories, for him to read. And he’d say, “I don’t understand this. I don’t understand that.” That had a great impact on my education. It taught me to be accessible.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.