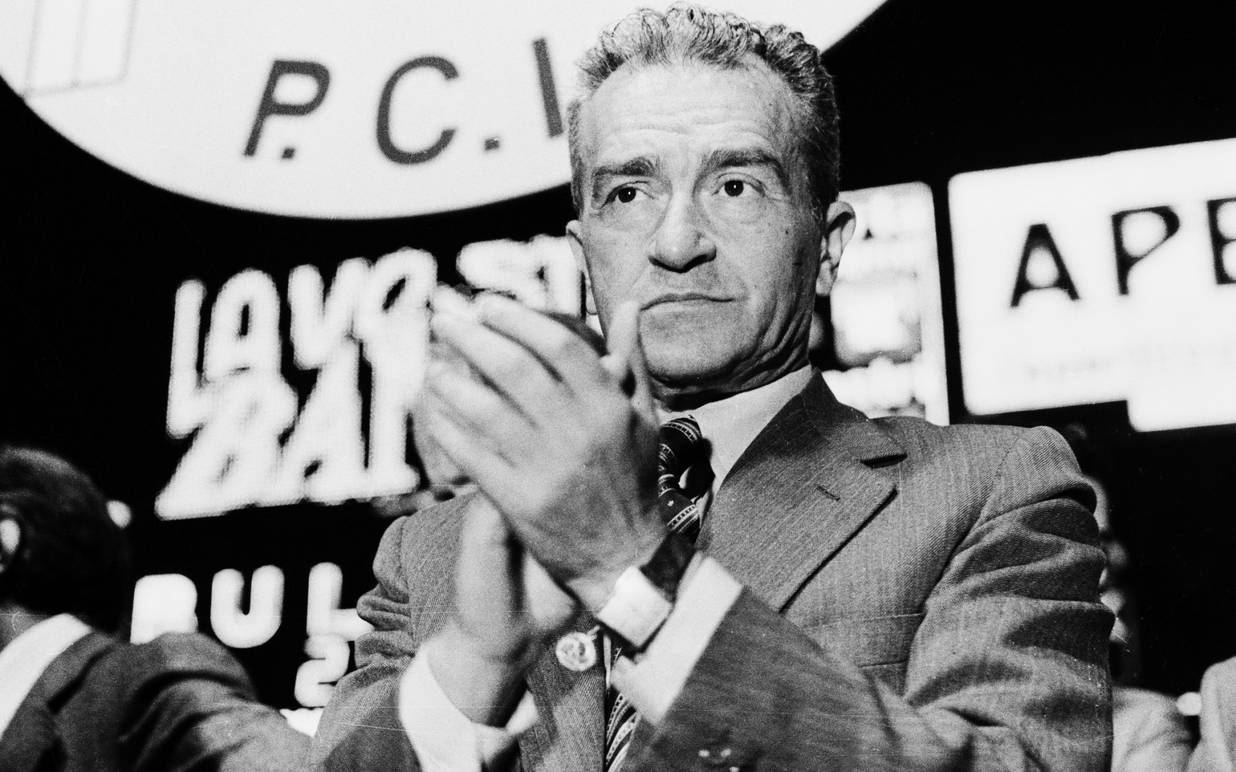

Pietro Ingrao. In Memoriam

When I was offered a job in the Centro della Riforma dello Stato in 1978, I felt I had hit the jackpot. The Director of the Center, a research outfit affiliated to the Italian Communist Party, was Pietro Ingrao, who was also the President of the Italian Parliament. At the office, he was Pietro.

I knew him only from TV. I had seen him in person only from the distance that separates the podium from a crowd of thousands at Festivals of L’Unita’. But I knew his speeches, and I loved his deep voice that always went deeper when talking about “the masses,” and his accent from southern Lazio.

I must agree with Fabrizio Rondolino, who yesterday has written inc that “Ingraism,” a political/philosophical position within the Communist Party inspired by Ingrao, was synonymous with an irreconcilable dissent, but a strange form of dissent, one that was all internal to the dynamics of a closed and conservative organization.

For many of us, who loved the ideals of social justice proposed by communism but did not like any realization of those ideals, Ingrao represented a solution: how to stay in the Party while feeling not completely ‘owned’ by the organization, in other words, how to continue to dream of a different world above the politics of the day.

It took me a while to feel comfortable with the idea that Ingrao was my boss, that I could see him everyday, from across the desk. He treated me with respect but also some diffidence. I was younger, inexperienced, and really not a good Communist. When we organized a prophetic conference on the demise of the mass party, my first thought was to convene the best political scientists, no matter their political affiliation. His first thought was, can we trust them?

I have precious memories of a few times I spent with him alone. I was obviously a groupie, but he never took advantage of this. On the contrary, he was always honest with me, and at times self-deprecating.

Once, I asked him about his experience of the anti-Fascist resistance and he told me of his attempt to escape from the police and cross the border to Switzerland. His story kept me on the edge of my seat, as he described the long trip from Rome to Milan, always in disguise. He was handled at different stops by a series of underground operatives, who gave him new passwords at every stop. In Milan, he knocked on a safe house’s door, gave his last password, and was welcomed by another partisan who presented him with an elaborate plan to reach the mountains, walk to the top and ski across the border. “I don’t know how to ski,” said Pietro. He returned to Rome the next day.

One late night, it was past midnight, he saw me in the center of Rome as I was climbing on my bike to return home. He had his driver stop his official blue car and told me I had to put the bike in the trunk because he would drive me home. It was not safe for a young woman to be alone in the street at that late hour.

I was initially irritated by what I thought was a paternalistic intervention, I was, after all, a free woman. But the drive home was something to treasure forever. Once again, the intimidating leader and statesman spoke honestly about being in fact paternalistic, but not enough. He forgot to take care of his wife and daughters for so long, being always busy with politics.

In 1981, having drifted away from the Party, I decided to come to the US and pursue a Ph.D. at Columbia University. Most of my friends were upset, some called me a traitor. I was afraid of telling Pietro that I was quitting, but I had to.

I gingerly approached the topic of my departure, but there was no need for caution. “If I were your age I would do exactly the same,” he said.

A few months later, when I was already in New York, he sent me a letter. It was after Jaruzelski’s coup d’etat in Poland. He wrote that this had been yet another blow to his dreams, the possibility that communism would not necessarily be hell on earth. He wrote me, I am paraphrasing now, that if he could, he would retire to Lenola, his home town, and listen to Beethoven.

Yet, when the Communist Party transformed itself after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Pietro left it and joined Rifondazione Comunista, the last incarnation of Italian Communism.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.