Italoamericana: Writing for a Cause

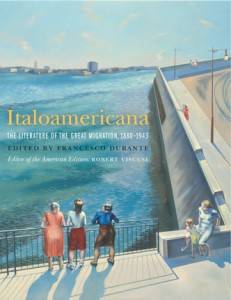

With his anthology of Italian writing produced in the United States from 1885 to 1942 circa, Italoamericana (Mondadori, 2005), Francesco Durante introduced Italy to a literary tradition — a canon — that was totally unknown to the Italian literary establishment.

A wake-up call for Italians

Like Gian Antonio Stella’s L’orda, quando gli albanesi eravamo noi (Rizzoli 2002), Durante’s anthology put Italy on notice. At a time when Italy had already transformed itself into a country of arrival, dealing with the coincidental issues of social misunderstanding and bigotry that accompany immigration, Italoamericana reminds Italians that their own citizens had left their country well over a century earlier and, in their new locales, faced innumerable trials and tribulations brought on by the citizenry of their host countries. It is, de facto, a wake-up call for Italy; how it now behaves — or does not — vis-à-vis its current immigration phenomena.

A true literary tradition

Yet, Italoamericana is more. It is proof positive that the immigrants who came to the United States was not the illiterate bunch that many would want us to believe. From fiction to poetry and to theater, we find a literary tradition that was vastly productive and, for the most part, aesthetically successful.

The creative writers were serious in intent — at times comical and sarcastic, other times sober and prescriptive — in dealing with their local surroundings as theme. What we thus find is the birth of a literary canon in Italian outside Italy. As far back as 1885, people here have been producing literature in Italian, that was also published locally, as there were numerous local Italian-language publishers.

The essayists and journalists, in turn, spoke to a variety of issues that plagued the Italian community at that time: analogous, indeed, to those that now plague the new immigrants in Italy. Gino Speranza’s essay (“How It Feels to Represent a Problem ”) discussed “how few Americans ever consider how very unpleasant, to say the least, it must be to the foreigners living in their midst to be constantly looked upon either as a national problem or a national peril” (52).

Alberto Pecorini (“The Children of Immigrants”) examined the conflict between immigrant parents and their children, where education and personal growth were strange concepts to the former.

Alfredo Tarchiani (“Neither Foreigners nor Americans”), similarly, spoke to identity: “The Italians of America are Italian-Americans and so shall they remain. They cannot dissolve their bonds of affection for their homeland regardless of how many naturalization cards they acquire or how many oaths they take. They can, however, be equally obedient, devoted, and productive citizens of the United States…” (72).

Indissoluble bonds of affection

Italian writing in the United States continues. One need only think of Peter Carravetta, Alfredo de Palchi, Rita Dinale, Luigi Fontanella, Irene Marchegiani, Elda Tasso, Joseph Tusiani, Paolo Valesio et alii.

These are some of the writers today who have lived here for numerous decades and have negotiated, each in his or her own way, themes analogous to our earlier authors; writers today, as Tarchiani said of his time, who “cannot dissolve their bonds of affection for their homeland regardless of how many naturalization cards they acquire or how many oaths they take.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.