Welcome to the Quirinal Palace

ROME – Do you have air miles or money to burn on airplane fuel? If so, take advantage and fly to Italy to pay a call on the 16th century Quirinal Palace, home to the kings and presidents of Italy for the past century and a half. As a culmination of this year’s celebrations of 150 years of Italian unification, the monumental doors to a series of magnificent halls, which overlook the main square on one side and the interior court of honor on the other, are being opened to visitors for an unusual exhibition, free of charge to all comers, to last just three months. His purpose in encouraging the exhibit, as the palace’s present occupant, Italian President Giorgio Napolitano, told visitors to the inauguration Nov. 30, is to welcome an ever vaster public from every walk of life, including scholars and school children, into what is “the home of all Italians.”

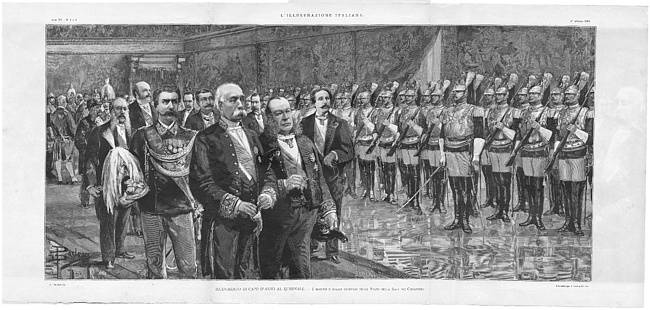

The exhibition mounted inside in the newly restored Napoleonic Wing of the building offersan occasion to view the palazzo itself but, more unusually, an opportunity to reflect upon and to study the past century and a half of Italian history, thanks to a rare collection of documents, photographs and period newspapers and magazines plus and some vintage newsreels assembled by curators Paola Carucci and Louis Godart. Its documents illustrate the various events which have taken place within the palace, from the installation of the House of Savoy (Sabaudi) monarchs through the Napoleonic period; the successive Fascist era up to and including the dramatic moments of liberations of Rome by the Germans; the abdication of King Victor Emanuel III after the monarchy was abolished in 1946; and the proclamation of the Republic of Italy in 1948 with adoption of the constitution. According to the architect who physically mounted the exhibit, noted stage designer Luca Ronconi, the documents mounted on glass panels “are an invitation to rediscover memories and a knowledge of events, many of which took place within these halls.” One example: during World War One the palace became a hospital for wounded soldiers.

The palace atop the Quirinal Hill (one of the seven ancient hills of ancient Rome) was built in 1583 as the summer residence of the popes, eager to escape the malaria-ridden low-lying area near the Tiber River, which includes St. Peter’s Basilica and its environs. In fact, during conclaves cardinals were taken ill with what was called mal’aria (bad air); the illness was recognized but not the cause. When victorious Italian patriots captured Rome, the Vatican State was reduced to the square mile it owns today, and the Quirinal Palace was part of the booty.

Like the carriage which the king rode to the World War I front, there is much to interest even those who cannot read the documentation.

A visit begins with the space itself: a sequence of vast connecting halls adorned with frescoed ceilings, precious tapestries, elaborate fireplaces and rare examples of antique furniture. Some early papal treasures are visible (only a few; the pontiffs took most of their belongings with them to the Vatican). Some of the paintings and objects from the early royal collections also date from the period (1800-1815) when Italy came under Napoleonic rule.

The real luxury is that all—most importantly—are seen in situ rather than transferred to a museum. Three essential periods are illustrated. The first begins with the breach of Porta Pia by Italian patriots in 1870 and installation of the first king of united Italy, Victor Emmanuel II (1861-1878. From this period comes one of the most interesting paintings, which shows Garibaldi, leaning on two canes, on a visit to the palace in the company of that first king. Another particular focus is the work of Queen Margherita, the wife of Umberto I, in organizing a library inside the palazzo.

The second period documents Italy under Fascism and includes some rarely seen paintings from the royal collection, such one by Giacomo Balla and a stunning Futuristic scene of Italian airplanes over Vienna by Alfred Gauro Ambrosi (1933). The third period dates from 1946 to the present, and includes such touching mementos as a letter written by the Red Brigades victim, the politician Aldo Moro, addressed to the president of Italy Giovanni Leone (1971-1978) asking his intervention with his kidnappers.

In the larger sense, rarely more than today has the Italian presidency, and the building which it symbolizes, performed the role of unifying force, capable of monitoring and managing what has become a fractious and stubbornly immobile n body politic. The role which the exceptionally popular President Napolitano has played in the current wave of political and financial crises has been fundamental in binding wounds and in binding together in the national interest often hostile political forces. For this reason alone the exhibition would be particularly important today.

“The Quirinal Palace from the Unification of Italy to Our Own Day,” Quirinal Palace, Free entry, through March 17, 2012. Tuesday through Saturday 10 am-1 pm and 3:30-6:30 pm; Sundays, from 8:30 am to 12 noon. Closed Mondays, and on Dec. 8, 18, 20-21, 24-26 and 31, and on Jan. 1 and 6.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.