"Bitter Bread" for the US. An Encounter With Gianfranco Norelli

We interviewed Gianfranco Norelli in the library of the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute, surrounded by books that seemed to be watching us.

It was an in-depth conversation about that aspect of America that is also Italian, the America that many Italian-Americans are still not familiar with. He told us about his large-scale project related to the documentary he has produced, written, and shot: Bitter Bread.

Through him the pages of history from the last century speak to the present.

We present highlights from our conversation-interview organized by topics. It’s a preview of the U.S. version of the documentary film that will be screened at the Center for the Performing Arts at LaGuardia Community College/CUNY in Queens.

Traveling in Italy

“While in Italy with my wife, who is an American citizen of Indian decent, we noticed a reaction that was disconcerting to say the least. On more than one occasion we witnessed episodes of suspicion, discrimination, and even racism against immigrants….” Gianfranco Norelli begins to tell us what led him to make the documentary "Bitter Bread" .

“I was surprised. I didn’t remember the Italy where I was raised to be like this. I have lived in the U.S. for thirty years, but I have always gone back for short periods. For some time there has been something new – an unexpected, offensive attitude towards immigrants. It is present even at the institutional level, for example, on the part of several mayors in northern Italy. There is little familiarity with the concepts of multiculturalism and diversity.”

A Documentary for Italians

And so Norelli, along with his wife Suma, decided to make a documentary to raise awareness about the difficult experience that Italian immigrants faced in America. An exceptional project with different points of view was born, one with a wide breadth and scope.

He is a journalist and a director who over the course of his career has made many important films, such as the documentary with Fabrizio Laurenti entitled Mussolini’s Secret. It tells the dramatic and little-known story of Ida Dalser which inspired the recent movie Vincere by Marco Bellocchio.

Immigration and Amnesia

Suma Kurien Norelli has focused on immigration for over twenty years. She teaches language and vocational training courses at LaGuardia Community College/CUNY. As a conscientious scholar of issues related to assimilation, she understands the situation in New York very well.

Her husband tells us: “Suma has noticed that in Italy there is a lack of awareness on the part of social workers who deal with immigration issues. They lack a universal vision. Bitter Breadwas created to inform more Italians about the forgotten pages of history that very often are not included in history books….”

This amnesia is caused by a deep gap between Italians and Italian-Americans: “They lost contact. Italians in America lost the opportunity to remember and examine their own history here, but also to keep up with the evolution of Italian society over the years.”

A Documentary for Americans and Italian-Americans

Bitter Bread was originally created for Italian television, but the Norellis soon realized that they would have to make another version specifically for an Italian-American audience.

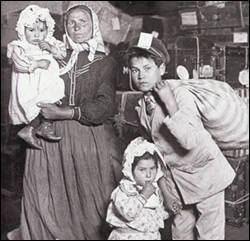

“Many of these stories were not known, even in the United States. We have shown it on several occasions to Italian-American audiences. Very few of them knew about the lynchings of Italians, for example, or the fact that Italians were seen as a mixed race, neither black nor white, or that Italian immigrants were initially recruited to replace enslaved blacks on southern plantations…”

How were these subjects chosen?

“My wife and I made a list of topics and we discarded the ones that had already been covered in other films. We wanted episodes that were little known or not even known at all. We also wanted to revisit some themes. For example, we wanted to talk about the labor movement and trade unions, the role of women, the presence of a distinct culture, one of intellectual development on the part of immigrants that was not recognized by official history.”

Universal Values of the Italian-American Experience

Norelli portrays the Italian-American experience in a surprisingly way; it is neither conventional, nor celebratory, nor self-referential. The film uncovers and captures the immigrant experience, and does so without pity or rhetoric. “One of the goals,” Norelli tells us, “was to demonstrate, through several concrete episodes, how this experience has universal value and relevance. It can be applied to other communities that have been discriminated against, that have had difficulty integrating, and that have paid a high price to assimilate, such as loss of their culture, language, and contact with their country of origin.”

Bitter Bread was also shown at the Bangalore International Film Festival in India. “Here in Bangalore,” they told us during the festival, “there is a constant flow of immigrants from poorer regions

because we are the information technology capital in the area. We are flooded with these poor immigrants who are causing our society a lot of stress….”

A Difficult Film

Up until a few years ago, Bitter Bread would have been considered a difficult film to make because of the subjects it tackles. Today the film, which is supported in part by NIAF, demonstrates a different way to look at these issues.

“I think the whole debate has evolved,” said Norelli. “There is a new a new outlook. It’s less defensive. This is because the phenomenon of immigration to America as well as migration worldwide has evolved. The debate has now expanded.”

Speaking with Norelli about this film is like talking about a delicate, fragile creature. It has grown slowly and steadily through a lot of care and attention. The version that will be presented this week at LaGuardia Community College/CUNY is the result of hard work.

“At first we just translated the film and then had it shown here to gauge the Italian-Americans’ reaction. We realized that it had to be balanced and re-adjusted. The narration was recreated, removing the aspects that were already obvious to most Americans.

It resulted in a clearer, more specific work. For example, we reviewed the relationship between Fascism and Italian Americans, or assimilation as a process of loss of identity and language.”

A Film for Young People

“We also had to organize a more linear narrative structure, one that could be easily used an educational tool. It was divided into nine chapters and the information is organized by theme. So for example a teacher could choose to talk about stereotypes and then find the information in one place. We also changed the pacing, and we accelerated many of the sequences by adding in more music. This was so that we could make it more engaging for a younger audience.”

Lynchings and Stereotypes

Norelli gave us an overview of the topics that the film covers: “We start with the history of lynchings, beginning with New Orleans, as the most important example of difference, discrimination, and racism. We address the issue of negative stereotypes that today still affect the lives of Italian-Americans – the propaganda that portrays them as ignorant mobsters, etc.”

East Harlem

“We go on to discuss the creation of Little Italy. We do not use the usual neighborhood on Mulberry Street as a reference point, but the one in East Harlem instead. By the ‘30s it had become the largest Little Italy with more than 90,000 people living there. It gave us political leaders like Fiorello La Guardia and Vito Marcantonio, who, unlike the first, is relatively unknown. Marcantonio became the voice, not only of Italian immigrants, but of the entire ethnic working class in America.

At that time there were few representatives from the African-American and Latino communities and he also became their voice. He was re-elected seven times and so for a long period of time he had an opportunity to draft laws to protect the poorest and the most vulnerable. He created an alliance of different ethnic groups along with progressive white Americans which has not existed since. We can perhaps see a glimpse of it now, in a completely different way, with Obama’s victory.”

Americanization

“We then focus on the process of Americanization, the high price that Italians paid for integration with respect to the loss of their language, loss of contact with Italy, as well as the loss of their regional culture.”

Settlement houses, which constitute a significant phenomenon, are also discussed.

“There were groups of volunteers who provided help with the language, jobs, and contacts in order to integrate immigrants into the larger society. They were mostly women, missionaries of sorts, who gave up their comfortable, upper-class lives to work from morning to night in poor neighborhoods. We chose to talk abut Harlem House where Italian immigrants received services.

In many cases it only amounted to a bowl of soup. There was not enough to eat in many immigrant families. It was this poverty, this desperation that drove them to organize into unions.”

And how did these social workers help with the Americanization process?

“They went into the immigrants’ homes. They insisted that they had to transform their habits and customs to become Americans. For example, they told them not to eat traditional foods, to use butter instead of olive oil. These are the interesting details that give a sense of change, but the most important factor was that in schools not only did immigrants have to learn English, but they could not speak Italian. Not even a word of Italian. Elderly people have told me that they have clear memories of the school principal ordering teachers to wash out their mouths with soap as soon as they said one word in Italian.”

The Anarchist Experience

The film also deals with Italian-American experience in terms of politics, the labor

movement, and anarchism. The film attempts to reexamine several events that are still difficult to recount.

“Yes, the film not only speaks of pages of history that many do not know, but it takes a few pages that are already known and presents them in a different way.

It is important to show, for example, that while Italians today are often considered as a block, as a conservative force, for many years they had a tradition of progressive political activism spearheaded by laborers and those on the left. There were over a hundred newspapers written by the Italian left [in the U.S.].

This progressive cultural and intellectual dimension was ignored by the dominant culture. To tell the truth, it was not only progressive, but at times it was even revolutionary, as in the case of anarchists. For this reason, it was stigmatized.”

It is a history full of sensitive episodes.

“Gaetano Bresci left [the U.S.] in 1900 [with the intention of returning to Italy] to assassinate King Umberto I of Savoy. Bresci was a textile worker in Paterson [New Jersey] where one of the most important and difficult pages in the history of the American labor movement and trade unions took place. There were about 25,000 textile workers there, many of whom were from northern Italy, which had a deep-seated anarchist tradition, such as the town of Biella [in Piedmont].

Another very clear case of erasing history is the attack on Wall Street. There is no plaque to mark the event, even though forty innocent people died in 1920. Today there are just [pock-marked] holes in the wall of [J.P.] Morgan Bank, but nothing is written there.”

The Extremist Movement

By analyzing this attack, we wanted to open a window onto the fact that there were also extremists. Sacco and Vanzetti were part of a group of Galleanists [followers of the Italian anarchist Luigi Galleani] but they did not participate in this attack because they were already in prison, accused of murder and robbery. And the evidence against them for those charges was not convincing either. Nevertheless we must remember that Sacco and Vanzetti were militants who believed that violence was necessary in certain cases. It seems that the bomb on Wall Street was planted by Mario Buda, another Galleanist who acted alone.

Immigration Past and Present

Norelli’s film invites us to become aware, to reflect on what is happening in both Italy and America, as well as to think about the striking similarities between the anti-Italian propaganda of the time and that of several anti-immigrant newspapers in Italy today.

“We must draw parallels between what is happening today. We see that there are some Italian-American politicians who are very critical of immigrants. Fortunately it does not mean that all Italian-Americans think this way. We need to reflect on the fact that certain Italian newspapers publish denigrating images of immigrants that are not so dissimilar to images of Italians published so many years ago here in the U.S.…”

The World of American Politics

Another theme is the Italian influence in the world of American politics. In the documentary we see a progressive Fiorello La Guardia who supported Roosevelt’s New Deal. Vito Marcantonio was, of course, even further on the left. One slogan from his election campaign said: “We have to take back the government from the hands of Wall Street.” It is a theme that is very relevant today.

We also remember Leonard Covello, who is even lesser known. He was the first Italian-American educator. A man of the highest order, he foresaw the future with his multi-cultural awareness and ideas about integration.

Women and the Triangle Factory Fire

The contribution of Italian-American women is also an important aspect of the film.

“We talk about the Triangle Factory fire. It is officially known as an event in which the majority of workers who died were Eastern European Jews. This is true, up to 60%. The remaining 40% were southern Italians. I spoke with several historians who are truly surprised: how were there Italian women? And this is not the only chapter in which Italian women have played a significant role. Very often they were important union organizers. It is a

bit of a reinterpretation even with respect to the phenomenon of the role of women and its significance.”

Religion

Norelli uses the Church of Harlem as a point of reference in order to consider the importance of religion to the community’s cohesion and self-defense. This is another vast theme that should be studied more thoroughly, especially the relationship between the Italians and the Irish who discriminated against them: “They considered the Italian’s faith to be almost pagan, less rigorous. Italians were forced to celebrate mass in the basement. It is enough to remember that although the Church of Harlem was entirely built by Italians, for 40 years it had parish priests who were Irish or German, but not one Italian.”

Enemy Aliens

There is another story that we know little about. “We also address the issue of internment of Italian ‘enemy aliens’ during World War II. It must be said that even for those who were not deported, life was difficult with the infamous label of enemy alien.” It is during this ugly period of American history that the abandonment of the Italian language increases even more. Italians were told not to speak the enemy’s language!

Norelli also alludes to the relationship with fascism. “Mussolini thought that Italians abroad could be a source of strength for his regime. And Italian-American relationship with Fascism brought about this huge misunderstanding. We must bear in mind that an Italian-American’s perception of fascism would have been very distorted by distance.”

Bitter Bread will be distributed in American colleges and high schools thanks to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs which has decided to support this project.

Gianfranco Norelli continues: “It is definitely important to have the film broadcast on television. But I must also say that today content can be circulated without going on television. For example online, with a series of screenings leading to distribution in schools can do even more. Above all, I would like to encourage people of all generations to have a discussion. This is the goal. The film can even be found on Amazon.”

We hope that a wide distribution within the U.S. can bring the film back to Italy, where everyone should see it, not jut television viewers.

This is especially true since Bitter Bread was produced for television two years ago, but it was broadcast at a time slot that was not suitable for young people: 11.00 pm.

This shows that much remains to be done to bridge the Italian/ Italian-American gap and to learn from the Italian experience abroad. It is not enough that many Italian newspapers have exposed the scandal that such a useful film as Bitter Bread was buried in the television schedule.

The documentary will be screened on Thursday, June 11 at 7:00 p.m. in the auditorium of the Center for the Performing Arts at LaGuardia Community College/CUNY in Queens. The Consul General of Italy Francesco Maria Talò will be present, and Professor Anthony J. Tamburri, Dean of the John D. Calandra Italian-American Institute of Queens College/CUNY will introduce the event.

The screening, which is free of charge, is organized by the Consulate General of Italy in New York, the Italian Cultural Institute, LaGuardia Community College/CUNY, the John D. Calandra Italian-American Institute of Queens College/CUNY, the United Pugliesei Federation of the Metropolitan Area, and the Italian Cultural Association of New York.

It is a new English version that has been realized with the support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the National Italian American Foundation (NIAF) and which will be distributed to universities and schools in North America and on the home video market.

Bitter Bread in Images-Captions

1. VITO MARCANTONIO LEADING A STRIKE LaGuardia’s electoral victory is made possible by the organizational and oratorical skills of a young man from Italian Harlem: Vito Marcantonio. Son of a carpenter, Vito is a protege of Leonardo Covello’s. He starts his political career running citizenship classes for Italian immigrants, the first step to being able to vote and having political power. When LaGuardia becomes Mayor, Marcantonio succeeds him in Congress. Marcantonio has a long career as a congressman. He is re-elected seven times for a total of 14 years and is the first political leader able to bring together a coalition of Italian Americans, Blacks and Puertoricans to fight for progressive causes. After World War II Marcantonio becomes a target of the anti-communist witchhunt and is investigated by the FBI. His political adversaries manage to defeat him by changing the borders of his electoral district, incorporating into it many non Italian American voters.... In 1954 Marcantonio dies of a heart attack in the street as he is returning home after filing his candidacy for another congressional run.

2. LYNCHING PHOTO: Thirty-nine Italian immigrants are victims of lynchings across the United States between 1886 and 1916. This photograph, taken in September 1910, shows the lynching of two Italians in Tampa, Florida. The next day it appears on hundreds of postcards. The largest lynching in the history of the United States takes place in New Orleans in 1891 and involves the murder of 11 Italian immigrants.

3. Picture of Angeline Orsini, an Italian-American interned for 6 weeks after the Enemy Alien Act was emanated in 1942. She was in possession of a short wave radio. From the English screenplay of the movie: "When the United States enters the war against Italy, Germany and Japan, immigrants from these countries who have not become American citizens are declared 'Enemy Aliens'.”... Among these, Italians form the largest group: almost 600,000. According to the new law, the so called Enemy Aliens are required to carry special identity cards and are subject to curfews. They are not allowed to own short wave radios, firearms, cameras or other items with which they could aid the enemy. The family of Angeline Orsini owns a grocery store in a small town in Delaware. They also own a short wave radio. Angeline and her father are arrested by the FBI and are inprisoned in an internment camp in New Jersey for six weeks. They have lived for many years in the United States without becoming citizens. They are among the 2,500 Italian Americans who are interned during the war, some for up to three months.The “Enemy Aliens” of Japanese origin receive a harsher treatment. Although many are US citizens, 120 thousand of them are interned for the entire duration of the war.

4. Picture from the movie "Il Lavoratore della seta" (The silk worker), 1917- The newspaper of the workers employed in the silk manufacturing industry in Paterson, New Jersey. The heading is one of more than 100 Italian newspapers released by Italian immigrants in the US.

(Traslated by Giulia Prestia)

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.