Of Emperors, Murders and the Ides of March: the Ghosts that Haunt Italy's Elections

On the ancient Roman calendar the Ides of March fell on our March 15. On that day in 44 BC the political problems of the Roman Empire were neatly resolved with the brutal assassination of the man who considered himself not only godly but indeed a god, the emperor Julius Caesar. The Roman senate building had burned and the Senate was temporarily meeting in the vast stone theater which General Pompey had built near today's Campo de Fiori in Rome, and so the self-anointed emperor Caesar died in what we would call today the lobby, at the foot of Pompey's statue. His murderers were his disgruntled fellow Roman senators, which is to say his political friends as well as enemies, united in their fear and loathing of him.

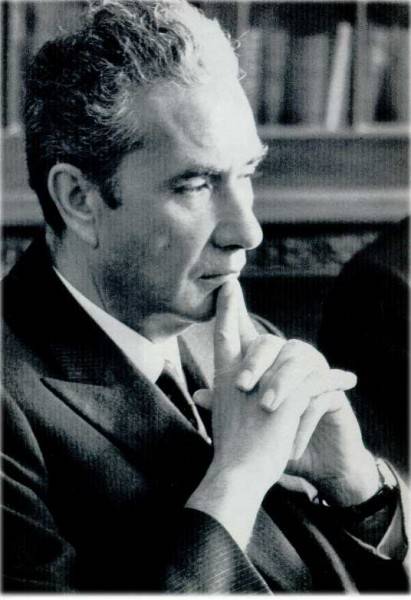

It is a bizarre coincidence that the kidnapping on a suburban Roman street of the most powerful Italian political leader of his era, the mildly progressive and astute Aldo Moro, fell nearly on the same day, March 16, just thirty years ago. Especially in Rome these days that kidnapping, with the professional-looking murder of Moro's five bodyguards, and Moro's own brutal murder fifty-five days later, are cause of serious reflection and commemorations, interesting if without any hint at a revival of investigations into whether among his disgruntled fellow Roman political aristocrats one may have had a hand in sponsoring the kidnapping.

In an interview which ran in La RepubblicaMarch 23, 1978, Leonardo Sciascia, whose novel Todo Modo foreshadowed the self-destruction of the Christian Democratic party, was asked by Alberto Stabile how he interpreted the kidnapping. Sciascia's reply: "The Red Brigades can be a monad [in biology, a monocellular organism] without a window, made up of violence and ideological folly, but they can also have doors and windows. If they have them, the problem is to see with whom they communicate; that is, to raise the question that Italians asked some years ago but which now they don't seem to ask any more: who benefits from this?" In my own interview with Sciascia, ever skeptical of power, ever curious, he said something of the same.

"Moro mattered to Italy. For twenty years he represented the democratic continuity of the Christian Democrats, " synthesizes Eugenio Scalfari. "With all his slow ways and the mistakes he made, Moro was the man who transferred the centrist party into its first alliance with the Socialists, and then made possible today's parliamentary majority which includes the Communist party" (by which Scalfari presumably meant the Rifondazione Comunista).

The Moro kidnapping was carried out by a handful of Red Brigades fanatics, and it was preceded by what is now a forgotten Brigades kidnapping, that of the son of the late Socialist leader Franceso De Martino. At the time Professor De Martino was aligned with Moro in promoting some form of an opening to the Italian Communist party, dubbed the historic compromise, in order to end a decade-long, frustrating political stalemate in government.

The legalistic and professorial Moro, notorious for both his subtle mind and the ambiguity of his political slogans, was a devout Catholic, but his party incorporated a strong Catholic farm worker and labor movement, with which Moro, who straddled the center, had some sympathy. His formula for suggesting discussions of an opening to the Communists was to counsel "parallel convergencies," a fuzzy phrase which puzzled and amused some observers at home, but absolutely terrified others outside Italy (read: Washington).

De Martino, like Moro, was a distinguished law professor noted for his personal honesty, and his version of the historic compromise was to urge "more advanced equilibriums," a phrase every bit as fuzzy as Moro's, but again, as with Moro, perfectly clear to those who made politics their business. In 1971 De Martino was a candidate and indeed the front runner to become president of Italy. He had the backing of the Communist party and the Socialists, but to be elected would have required a two-thirds vote in Parliament; without the Christian Democratic vote, he could not have been elected. So what would the Christian Democrats do, when it came to a vote? Many wondered: the party's left wing might split with its right and vote with the Socialists and Communists in favor of a Socialist president who, like Moro, was already advocating "more advanced" political agreements that would bring the Communists a share in power.

No one will ever know whether or not leftish parliamentarians within the Christian Democrats would have broken party ranks to vote with the Communist-led left, for it did not come to a vote. The Red Brigades kidnapped De Martino's son, who (like Moro later) was held for ransom. De Martino resisted for a time, but in the end he felt obliged to save his son's life by paying a ransom. Having little money of his own, he was offered and then accepted gifts of vast sums of cash from "friends." This obliged De Martino to withdraw his candidacy as president of Italy. Not long afterward he was replaced as General Secretary of the Italian Socialist party by leaders of another stripe, culminating in the corrupt Bettino Craxi and the demise of the party itself, just as the murder of Aldo Moro began the process of destroying the Christian Democratic party.

It was subsequently revealed that De Martino's staff had included a number of junior members of the notorious renegade P2 Masonic Lodge, whose other members included 40 individuals of high rank in the Italian military and intelligence. In short, the 1970s were not noted for their limpid politics. And, in the end, both the Italian Socialist party and the Christian Democrats, forged out of the collapse of Italian Fascism and the desolation of war, can be said to have died with De Martino and Moro.

What is the connection? Like most others who lived through the Italian "years of lead," I can only guess, but the fact is that guessing is not good enough. That said, to the historical record I wish to contribute two small items of evidence. The first is that De Martino whispered, just once, to a close colleague, "They took money out of one drawer and put it into another." Who "they" were he did not say, but by this he meant those "friends" who had given him the ransom money which then financed the Red Brigades future activities. My second small contribution to the record is that a source deeply involved in investigations into the terrorism of those years said purposefully after due thought, "The De Martino kidnapping was a trial run for the Moro kidnapping."

Think about it.

Unlike Professor De Martino, those in charge in both party and government determined that it was unacceptable to negotiate with the Red Brigades for Moro's life because doing so would give the terrorists recognition and authority. A minority thought otherwise: among those favoring negotiations was the Socialist leader Bettino Craxi. Most importantly, Pope Paul VI made an appeal to the Brigades, irritating many in the no-negotiations camp by addressing them as "Men of the Red Brigades," since to acknowledge them as " men" was seen by many as the pontiff's giving "monsters" (as a lot of people even on the left thought of the kidnappers) undue recognition of a common humanity. And perhaps some negotiations were afoot, or at least contacts, for a cache of copies of letters from Moro, which turned up mysteriously many years later in Milan, suggested that contacts with his family may have existed. If so, go-between therefore existed: who? Presumably a clergyman. But if one person could find Moro, so, it can be argued, could others.

Not long before Moro was murdered I received a telephone call with an offer of an interview with a Brigatista. I replied that of course I was ready and willing, but that I would not come alone: I would come with half the Italian army. The phone went dead. So, of course, did Moro. Who was the "terrorist" I was to interview? I never knew.

Not long afterward I was again contacted, this time by an America who occupied an official position. Could I kindly, he asked, "for a journalistic friend," arrange an interview with a Brigatista? Before I had time to think I snapped, "Sure. It will take place in my living room and I will wear a ski mask. It will cost $10,000. You get half." Again, the phone went dead.

But elsewhere the voices were speaking: the voices of children in the park, playing the kidnapping of Aldo Moro. The voices of people frightened in the streets. To recall the collective fear of those long days still leaves me gasping. And the day in May when Moro's body was found in a car parked only a few blocks from my own home I knew what had happened immediately because a thousand sirens were screaming at once. Like others I ran as fast as I could, and, since I was only blocks away, I was there to see the end of his personal drama -- but not the end of Italy's, which is still recovering.

And so to the present. Wreaths and conferences and press symposia on the significance of these three post-Moro decades have, yes, commemorated Moro, but above all have asked whither the Roman Catholic vote in the forthcoming elections, scheduled for April 13-14, to take place, shamefully, after less than two years since the last elections. Those of Spring 2006 were won, all too narrowly, by a helter-skelter, fractious coalition of leftists, including a miniscule if noisy Communist party plus Greens and Radicals and Social Democrats, all supposedly unified, but in fact increasingly at war among each other, under the leadership of two who in a way reflected the Moro dilemma: the devoutly Catholic Prime Minister Romano Prodi and Fausto Bertinotti, the head of the Rifondazione ComunistaItaly's situation, but other forces did their best to tear down whatever reforms were attempted. party. It simply did not work. The economists involved did their best and have improved Italy’s situation, but other forces did their best to tear down whatever reforms were attempted.

So now what? The Italian Church appears to have been quarreling with the Vatican itself over the degree of interference to be tolerated, with the Vatican trying to calm over-excited local bishops. As for the Roman Catholic voters themselves, their vote is split. Walter Veltroni, until last month the Mayor of Rome and now the leader of the new Democratic Party (which supplants the Party of the Democratic Left), is working hard to forge a coalition that embraces ardent Catholics as well as libertarian feminists, among other unlikely bedfellows, resulting in a schizophrenic politics in which making abortions tougher to get is high on the agenda and any notion of gay rights is dropped.

Will the new elections bring change? It is sad that the logos of twenty-seven parties will appear on the ballot, but some here believe that "eppur si muove," to synthesize in the words of Galileo. By this is meant that it is positive that Veltroni, a moderate progressive, and media emperor Silvio Berlusconi, the former conservative prime minister, are forcing creation of two strong parties to replace the thirty-some ever quarrelsome groupuscules of the outgoing Parliament. It is eagerly to be hoped that it will work.

However, among the crucial elements missing from the programs of both these leaders is any proposal for an all-out battle against the ever more powerful forces of organized crime and its attendant political corruption. Since crime here still defines the political class (to wit., the garbage of Naples), this oversight, as we shall call it to be polite, is deadly serious--literally. Whatever the memorial wreaths symbolize, it does no honor to the memory of Aldo Moro or of De Martino either.

This article appeared originally on DIRELAND and is re-published here with the permission of its editor Doug Ireland.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.