Wolfgang Achtner? Chi era costui?

Whereas unashamedly biased mainstream “journalism” is quite a recent reality in the United States—one can make a strong case that US news media environment changed with Rudolph Murdoch’s launching of Fox News—Italians cannot blame Silvio Berlusconi’s media empire for their lack of an independent press.

Specifically, Italian TV news reports have had a slant since its outset; their characteristic “pastone politico” (political oatmeal), where unnecessary close-ups of prominent politicians of the moment invade the meals of Italians, is rather unique to Italy’s mode of TV reporting.

So after the fall of Berlusconi’s government and the subsequent nomination of a technocrate to Italy’s Prime Minister, Mario Monti, Wolfgang Achtner, a US born journalist who spent most of his life in Italy, decided it was time to change how video journalism is done in Il Belpaese. And last December, Achtner presented his self-candidacy to the direction of RAI TG1.

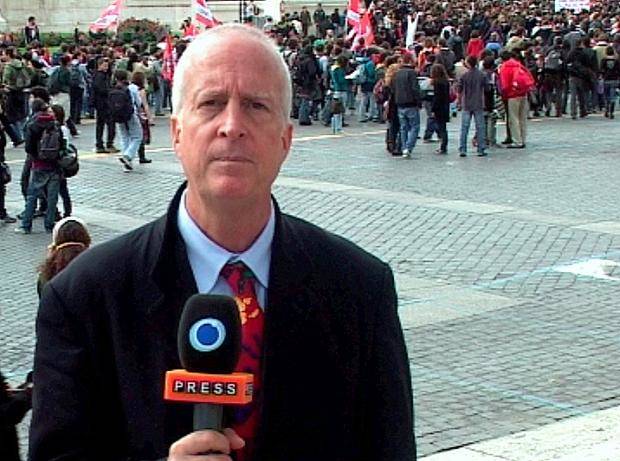

In his thirty year-long career, Achtner has been a correspondent for CNN and PBS, reporter/producer for ABCnews among others, and he has worked in print, radio and extensively in documentary filmmaking: he is the author of several documentaries—most recently, La primavera dei movimenti on the “movimento dei girotondi”, the social movement spearheaded by director Nanni Moretti, and Sabato a Roma on the largest protest ever held in Italy, the one that took place on March 23, 2002, in Rome, where millions of people gathered against terrorism and in defense of workers’ rights. Achtner is also an educator and the author of the only textbook about video journalism published in Italy, Il reporter televisivo (McGraw-Hill 1997).

Though only two major Italian news media outlets (the online version of Il Fatto Quotidiano and the news magazine l’Espresso) have reported Achtner’s self-candidacy, he is supported by several online-driven citizens’ and reporters’ movements, such as Il Popolo Viola, MoveonItalia, Avaaz.org and Articolo 21.

“I could have never done this six years ago,” Achtner says. “It wouldn’t have been possible to organize such a nationwide campaign.” In the era of social media, all he needed was a laptop computer with an Internet connection.

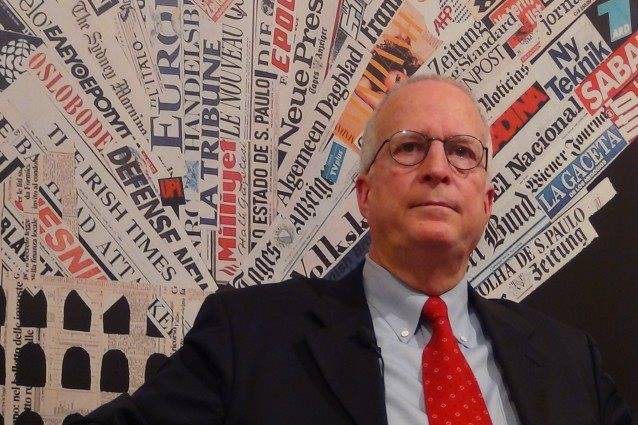

Wolfgang Achtner, 61, was a backpack journalist long before the term was even coined. As a video journalist, he shoots, interviews subjects and edits his own work. Achtner is a one-man show, and if you spend longer than thirty minutes in his company, he lives up to his reputation.

Achtner has an uncurbed tendency to monopolize the conversation, so to say that I had an interview with him recently would be like saying I had a conversation with the priest while attending Mass on Sunday.

Yet, Achtner knows what he’s talking about. And, as many Italians, is angry. He also seems sincere when he says that he would like to see change happening in Italy, which he defines as “a feudal-closed society [where] the people in power (…) maintain their own power by limiting access to finance and information and jobs.”

So he decided to be proactive, and, given his impressive qualifications for the job, he shot for one of the key positions in the system: because to change Italy, you have to begin with changing its news media system.

Achtner says he saw a “window of opportunity” for his candidacy to the direction of TG1 at a time when “the political system is terribly weak.” So Achtner wrote a letter to president of RAI “Consiglio d’Amministrazione” (Administrative Council), Umberto Garimberti, and, most recently, along with its supporters at MoveOn Italia, one to Mario Monti himself.

And here lies the rub. Since its outset, the national public television has been regulated by “lottizzazione,” the practice of assigning positions of power among political parties within the public service broadcaster according to the parties’ performance in the last national elections. Achtner doesn’t have any political affiliation.

“If you control the newscast, you control the electorate,” Achtner continues. “(…) “People who are not really informed, don’t vote freely.”

Recently, the advent of social media and the proliferation of blogs have altered the extent of control over information and news circulation in Italy; yet, the majority of people still get their news from television, especially in a country with such an old population like Italy. And, as Achtner points out, very few Italians speak English and get any exposure to the international standards of TV journalism of BBC, Al Jazeera and the like.

Achtner says that his travels have shown him “the inextricable connection between freedom, democracy and a free press.”

“For most Italians, TV news is not only the first source of news,” Achtner adds. “But it is also the only source of news!” (my emphases)

In post-Berlusconi Italy, and in the aftermath of Augusto Minzolini’s direction of TG1, this very fact mandates a drastic change in the management of national public newscast.

Achtner laments that the direction of Italian “TGs” has been offered to journalists whose primary expertise was in print, not in video journalism. Achtner equates such a choice to having a “truck driver at the control of the jumbo jet.” But he also comments bitterly: “They (the past directors) didn’t have to know or have any particular skills…Their only function (…) has been to protect the particular slant the news they were supposed to be given according to their political sponsors.”

On Jan.28, Alberto Maccari was reconfirmed as TG1 interim director, but a new RAI Administrative Council will be formed in April, and Achtner hopes to still have a chance.

So what is Achtner’s plan in case he pulls it off and gets the job?

“Turn that camera 180 degrees away from ‘Il Palazzo’ and onto the country.”

He believes Italians need to reclaim what has made them famous all around the world: craftsmanship. “Italians used to take pride in their work,” he says. And he admits there are still many journalists out there who know how to do the job. “Journalism means public service,” he says. “You need to be like a priest. A journalist is supposed to do a job that helps society work better.”

Cosmetic change won’t save Italy. And, if you ask Achtner, the time to act is now; or never.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.