Giancarlo Caselli: Sciascia and the Palermo anti-Mafia Pool

ROME –Giancarlo Caselli is a hero for our time, and a witness to the events of the bitter Palermo season of 1992-1993, when judge Giovanni Falcone, prosecutor Paolo Borsellino and their police escorts were brutally murdered by the Mafia. In the background of those deeply disturbing events was a puzzling intervention by the great Sicilian writer Leonardo Sciascia.

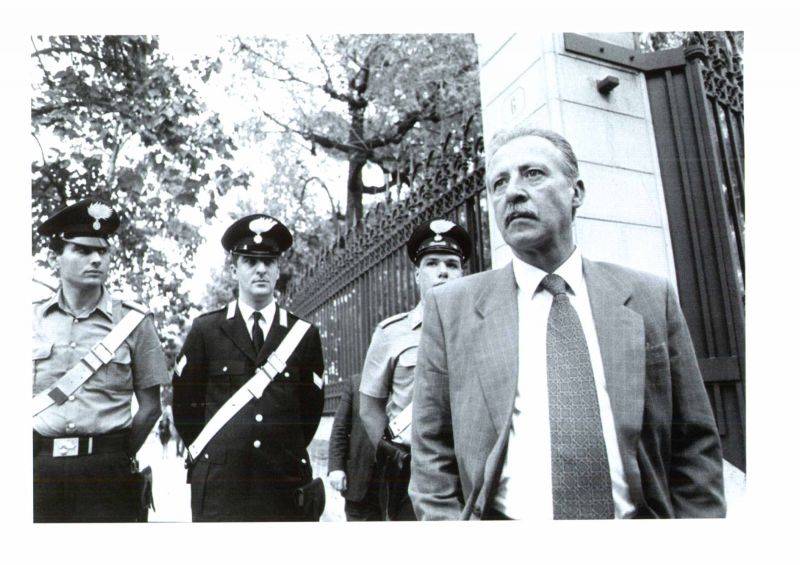

Caselli has unique experience in Italian jurisprudence. Having survived the years of lead as a judge investigating leftist terrorism in North Italy in the Seventies, he became chief state prosecutor in Palermo in 1992. When Caselli arrived there, hundreds of mafiosi were in rigid maximum security prisons as a result of the record number of convictions brought in the famous “maxi-trial,” brought by a pool of magistrates including Falcone and Borsellino in the 1980s. More went to prison under Caselli, who put Mafia bosses like Leoluca Bagarella behind bars and was also responsible for the arrests of two mafiosi who have since made important revelations to investigators, Gaspare Spatuzza and Giovanni Brusca.

In consideration of his experience in combating the Mafia, in 2005 Caselli was the front-runner to become Italy’s chief anti-Mafia prosecutor. But just then the center-right Parliament passed a bill placing an age limit on the post. This new law neatly eliminated the candidacy of Caselli, born in 1939. Instead he returned to his native Turin in April 2008 as chief state prosecutor there.

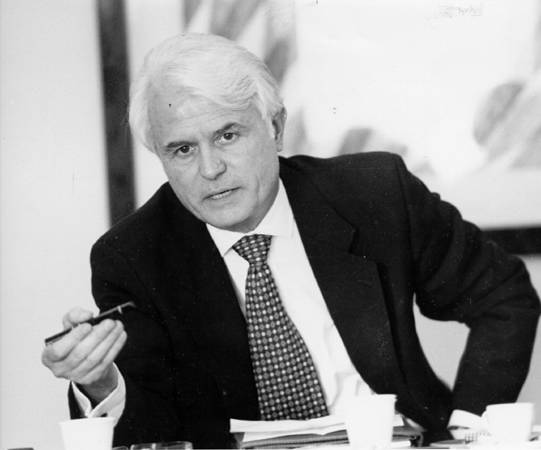

Two alarming precedents also involved nominations of anti-Mafia investigators. According to Caselli, writing Nov. 12 in the leftist daily Il Fatto Quotidiano, some years after the maxi-trial Borsellino requested a transfer from the Palermo anti-Mafia pool of judges to Marsala, on the western Sicilian coast, where he hoped to take over as chief prosecutor. His rival for the post was a magistrate who had never tried a single Mafia case, but had the advantage of seniority—never mind that Marsala, like Palermo, was Mafia turf. In short, the choice was between a tried Mafia expert magistrate with experience in the pool, and a man who had served more years in the magistracy. Which was it to be?

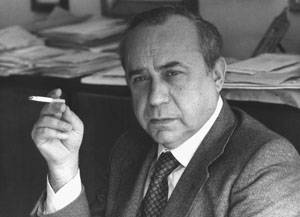

At this point the national daily Corriere della Sera entered the fray, publishing an article by Leonardo Sciascia, entitled “The Anti-Mafia Professionals.” In it Sciascia attacked Borsellino by name. In consideration of Sciascia’s authority in matters Sicilian, this was like Moses setting down a law. “Sciascia was a giant,” writes Caselli. “But this article was a stunning error, and the cause of permanent damage. To speak of Borsellino as an ‘anti-Mafia professional’—implicitly an ambitious man bent on elbowing his way past a worthier colleague—was absurd and completely implausible.”

Years later, Caselli continued, “Sciascia acknowledged that he had been badly informed.” The suspicion then is that, in a tragic irony, the normally suspicious Sciascia was himself set up to write the article, which continued to be ruthlessly exploited as the attacks on the purported “anti-Mafia professionals” continued unabated. “The next to pay the price was Giovanni Falcone,” Caselli writes.

In 1987 the senior magistrate who headed the pool, Antonino Caponnetto, resigned to return home to Florence after four years of living under protection. “Caponnetto left Palermo convinced that Falcone would be his successor.” But here too there was a rival, who let it be understood beforehand that the successor planned to disintegrate the anti-Mafia pool, says Caselli. Falcone too was presented as another headline-grabbing anti-Mafia “professional.” The seniority clause was dragged out again, meaning that the winner would “not be the most qualified in the anti-Mafia team.” In the end Falcone became a victim of mud slinging to the point that he was forced to quit Palermo.

Caselli’s conclusion: “The investigations into Cosa Nostra were shredded into a thousand pieces. No longer were there communication and exchanges of information among investigators….One step from victory the battle was surrendered.”

From evidence emerging only now from a number of sources, including Spatuzza and the son of the convicted Mafia member and former Palermo mayor Vito Ciancimino, at just that time the Mafia urgently sought an easing of the harsh prison regime for the convicted mafiosi. To obtain this result the Mafia reportedly waged a campaign of violence that killed Falcone, Borsellino and their police escorts. Subsequent contacts that allegedly took place between Italian secret servicemen and Mafia bosses brought the massacres to a halt—so goes the theorem under analysis today.

It is at least a fact that, on November 6, 1993, harsh conditions for 140 convicted mafiosi were revoked—by exactly whom is now being investigated. But in the meantime first the anti-Mafia pool and then Falcone and Borsellino were eliminated—though not the Mafia.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.