Salina at the United Nations: How Italy Made the Small Powerful

One of the most noted moments of Paolo Fulci’s historic career as Italian Ambassador to the United Nations (1993-1999) brought international attention to some of the smallest islands in the world, starting with the Aeolian archipelago—one of the islands, Salina, is the place he calls home.

Ambassador, can you give us a brief version of that story?

It was not an easy time for Italian diplomacy. Germany and Japan were exerting pressure to reform the UN Security Council, which would have irremediably marginalized our country from the group of nations that really counted. And not only Italy but also the whole European Union. Almost all the major powers supported our opposition.

Luckily, it was a reform that had to pass through the General Assembly, where every country has a vote regardless of their GDP, military might, size, or population. So I decided to form a partnership with smaller, insular states, the so-called Coffee Club, thirty-two countries that generally had no say in the goings-on of the ‘big’ countries. Out of that, a mutually advantageous relationship was born, and in the end we were successful!

When I would participate in meetings, some diplomats from rival countries would make fun of me, asking me how I could diminish Italy to the level of a small, insular state. Nonplussed, I would answer that my home was in Salina, in the Aeolian archipelago, and these islands had the same problems as the small insular countries in the Caribbean or the Pacific: coastal erosion, out-of-control tourism, lack of transportation to the mainland, difficulties with the water and energy supply. And so I could give some useful advice.

Those same naysayers changed their tune over time, when they saw how, thanks to this alliance, Italy succeeded in blocking that unjust reform. In 1998 we even organized a gala evening at the Waldorf Astoria where, under the prestigious direction of the great Aeolian-American judge Edward Re, the ambassadors from our coalition met a delegation from the Aeolian Islands in front of 1,800 guests. It was an unforgettable evening and extremely important for our victory over the Germans and Japanese for the Security Council.

To face the ‘battle’, you recruited a number of influential figures from the Italian-American community. Many of them were at the Waldorf Astoria gala that night. That kind of involvement had not occurred in many years. What gave you the idea and how did it turn out?

Back then the Clinton administra-tion was ‘enthusiastically’ in favor of German and Japanese entry into the Security Council. And so it was against our position. So I thought that the Italian-American community could exert some pressure. You are talking about millions of people, many extremely influential in American politics.

It really did not take much to mobilize them, since they feel such a deep connection to their roots. I remember that at the Columbus Day Parade there were protest signs asking President Clinton to show Italy more respect in the UN. And the White House received thousands of faxes and telegrams from Italian-Americans expressing their anger over the way certain Washington officials were treating our country. I still remember one of the messages. [It read:] “Mr. President, we have been informed that some State Department officials are supporting a reform in the UN Security Council that would allow Germany and Japan entrance as permanent members, leaving out our country of origin, Italy. Be advised, Mr. President, that if this were to pass, it would be considered a literal smack in the face to 24 million Italian-Americans.”

Even then Archbishop of New York John O’Connor, during an homily in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, commented on the situation with great aplomb: “Who would ever have the courage to tell St. Francis of Assisi, Thomas Aquinas, Dante, Petrarch, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Guglielmo Marconi and Enrico Fermi that Italy could not join the Security Council because it had nothing to offer?”

You are originally from Messina, and have been an adopted Salinian for decades. What ties you to Sicily and Salina in particular?

My love for the Aeolian Islands goes back all the way to 1943, the year that the American troops landed in Sicily. My father, Sebastiano Fulci, who was an engineer with the Genio Civile, was tasked with starting the first infrastructure projects–building small piers, reservoirs, roads – that helped transform the beautiful archipelago from a remote land into the welcoming slice of paradise it is today. That year I began to enjoy the wondrous and extraordinary landscapes of Lipari, Canneto, Filicudi, Panarea and, naturally, Salina, whose malvasia really was ‘the nectar of the gods,’ as they call it. I returned to the Aeolian Islands many times over the following years, until one day my wife Claris and I discovered a white building in Salina called ‘Casa alla Palmara.’ We loved it so much that we eventually bought it and renamed it ‘La Clarisita.’ Since then we try to spend a good chunk of our summer vacation there every year.

What does it mean for a diplomat to come from a territory surrounded by the sea, from which so many men and women emigrated in search of a better life? Do you yourself feel a bit like an emigrant?

I was very lucky compared to the thousands of emigrants forced to leave Sicily after the Second World War to find work in more prosperous lands. But I can never forget that era when our fields were emptying out, left to desolation and poverty. Even though my job moved me quite young to Rome and then abroad, I could never leave my roots behind. In fact, living abroad, especially far away, strengthens your ties to your homeland, to the point that, even when I was in Japan, I would travel thousands of miles every year to return to my beloved Sicily with my wife and small children. The flight from Tokyo to Rome was endless—it lasted 24 hours!

Salina has a very particular history of immigration, as detailed in the Aeolian Emigration Museum founded and run by Professor Marcello Saija. Can you briefly give us a sense of that history?

Thanks to his extraordinary passion and dedication, Marcello has really given a soul and a spirit to these migrations. He has collected thousands of documents and photographs on Aeolian immigration from the end of the nineteenth century in North and South America to the post-Second World War migrations to Australia and New Zealand. And he retraced the paths and journeys taken by immigrants, all the sacrifices they made, and how they were finally able to find success.

You have a special relationship with New York City. Not only did you live here when you were Ambassador to the UN, but you also worked as vice-consul here in the beginning of your career. And before that you came to Columbia University as a Fulbright scholar. It is difficult to imagine such disparate experiences: The fascinating, frenetic city that never sleeps... and these minuscule, wind-beaten islands bursting with flowers and surrounded by water. And yet something must tie you to these territories, these landscapes. What is it?

It’s true. After Sicily, New York is probably the place where I have lived the longest. One year as a student, two as vice-consul, and seven as Ambassador. I almost feel more comfortable in New York than in Rome! But I always remember my Sicilian roots. When I arrived in New York as a young student in June of 1954, the first thing I did was look for my fellow ‘countrymen’ from San Filippo del Mela, a quaint little town just north of Milazzo. Those people knew my forefathers. They threw a wonderful party for me. It was my ‘initiation’ into a varied cosmopolitan world made up of so many different people. That’s how New York appeared to me when I first arrived.

What are the places that you love most in Salina, the ones that you miss most while traveling around the world as a diplomat? Tell us something that could persuade Americans to come visit this small Mediterranean paradise.

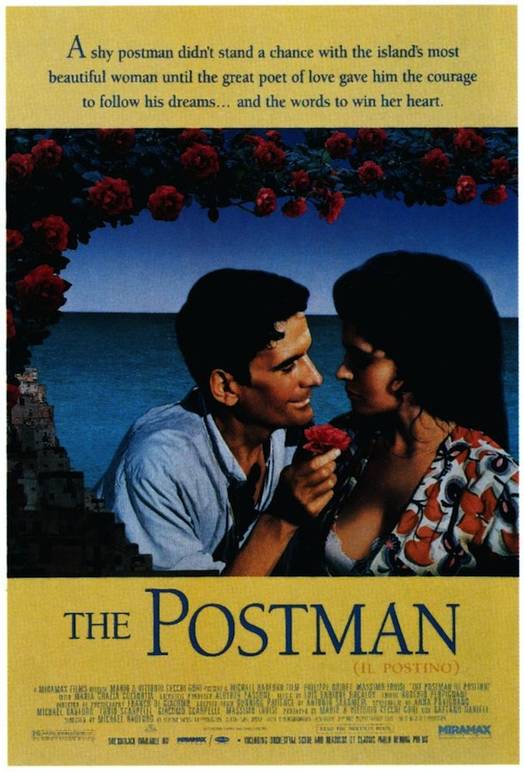

I love absolutely everything about Salina… Obviously my house the most; it’s situated on the edge of a forest reserve on an isolated promontory. It’s not easy to get to, especially when the sun is at its peak. I really love Pollara, the crater of an ancient volcano half immersed in the turquoise waters of the Tyrrhenian Sea, where the house for the film Il Postino (The Postman) is located. But above all I love the Rinella area and the unforgettable sight of its slopes in May, when they’re covered with gorse. The yellow flowers are so striking against the blue sea.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.