Roberto Saviano Between the Lines

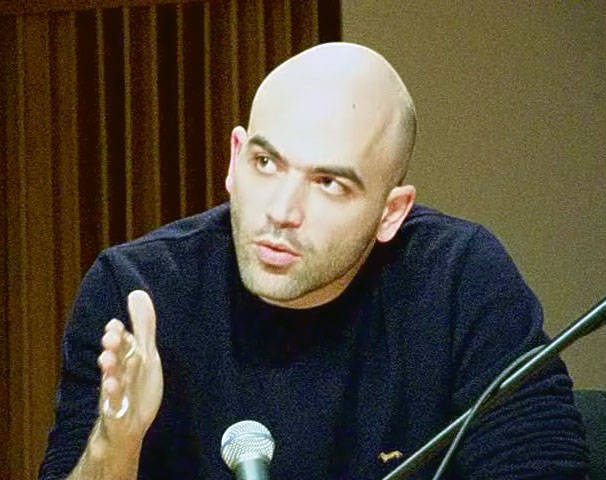

Roberto Saviano could very well be a thug. Next to Antonio Monda, the bespectacled NYU Professor who interviewed him Thursday evening, and who sat with legs crossed and gingerly fondled a book in his lap, Saviano had every bit the appearance of a man rougher around the edges, hardened by a certain experience. It was as though the years he spent embedded in the Camorra were reflected in his every gesture: the way in which he fixes a listener, almost threateningly, sits leaning forward with his elbows on his knees, or licks his lips when he speaks. With his bald head, deep brows and street swagger, he was only at a shade’s distance from an identical portrayal of the rapper Common in “Street Kings”. If the audience who had come to hear him speak for the PEN/Faulkner series hadn’t known better, they might not have recognized him as the best-selling author, household name, or courageous journalist that he is.

Saviano has risen to fame for that very courage (a term that’s being liberally applied to other figures in the Italy of late, namely Beppe Grillo and Walter Veltroni), with the publication of “Gomorra”. The book is an account of the Neapolitan mob’s, or Camorra’s, inner-dealings that controversially straddles the line between fiction and non-fiction—running the author into quite a bit of trouble. Following the wide-spread acclaim and popularity for “Gomorra”, Saviano received a litany of death threats from the mafia and has since been granted a permanent security detail from the Italian government. He spoke to Monda about this and more during an on-stage interview in front of a predominately Italian crowd.

Saviano’s explanatory manner was intense. When speaking about his birthplace, Naples and its constellation of outlying towns, he seemed to be saying, with reserved dismay and anger, “you don’t know what it’s really like”. When Monda asked him how he reconciled the beauty of Naples with its hellish dimension, one extensively rendered in his book, Saviano replied that it was naïve to see the city, as an Englishman once said, as merely “a paradise inhabited by devils.” As if suggesting that there were a false distinction between Beauty and Evil, he reminded that within the perceived Neapolitan despair was the pulsating heart of the place’s economy, the drug trade that generates hundreds of thousands of euros a day.

Money, Saviano went on to say, is what drives the Camorra unconditionally. He recalled a telephone conversation between two bosses the day after September 11th, 2001, in which the collapse of the Twin Towers had been talked about as an opportunity to buy real estate cheaply, or secure contracts for construction work, and never had the tragic nature of the events been mentioned. Indeed, all throughout his interview, the author was skilled at conveying, in a grave and highly articulate manner, the calculated barbarity he encountered in the Camorra men.

That same ruthlessness, murderous and business-like, surfaced in a number of episodes—gangsters proving they were tough enough by killing off their own families, the reckless disposal of trash by Camorra factions in the Neapolitan region , the assassination of a local priest who spoke out just one too many times. And what is potentially scarier than the criminal acts themselves, like in all mafias, is the pervasive nature of the organization’s activities, how the Camorra, similarly to the newly-powerful 'NDrangheta, has its hands in a wide variety of enterprises and a stranglehold on southern Italy. As Saviano described, the Camorra and 'NDrangheta have overshadowed even Cosa Nostra in Sicily because of the structure of their networks: an expansive alliance of powerful families or groups, rather than the pyramidal, hierarchical structure of the Sicilian old guard. The funds that power this new wave of criminal organizations are sometimes born of shadowy business practices whose legality is ambiguous, making it all the more difficult to stop the killings, the drugs, and the perpetual psychological terrorism.

After listening to Saviano speak for an hour, one had the impression of having been led by the hand through a shop of horrors. It was the very personal way in which the writer elaborated the events of his book, embracing and dissecting the depravity, sometimes in awe of it, like a guide who is connected to the place but also in sorrow for it. In the context of his work, and his own upbringing, the quote from Camus with which Saviano answered one of Monda’s questions rang true: “There is Hell and there is Beauty, and as far as I’m concerned I want to remain faithful to both.”

An enduring image from the evening, as told by Saviano, is appropriately infernal and dark. Neapolitan children, he said, had taken to selling skulls they would find laying on the banks of rivers (where the Camorra lawlessly disposes of garbage, including dead bodies), at the going rate of 50 euros for skulls with black teeth, 100 euros for those with white teeth. The notion of body parts for sale as a normal commodity conjured thoughts of a nightmarish underworld in which not only was there perhaps no state, no laws, but also no God. Saviano ruefully concluded that even the religious were beginning to lose hope. The outspoken priest who would later be killed, had once said at a funeral with his townsfolk “I don’t care to know who God is anymore, what I do care to know is what side he’s on.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.