Book Presentation: Lost Words, Coming of Age in 1970s Milan

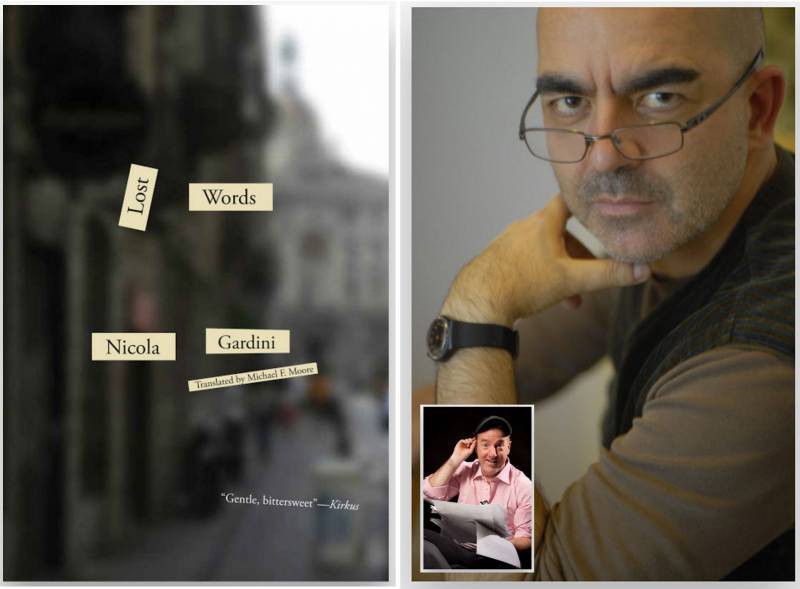

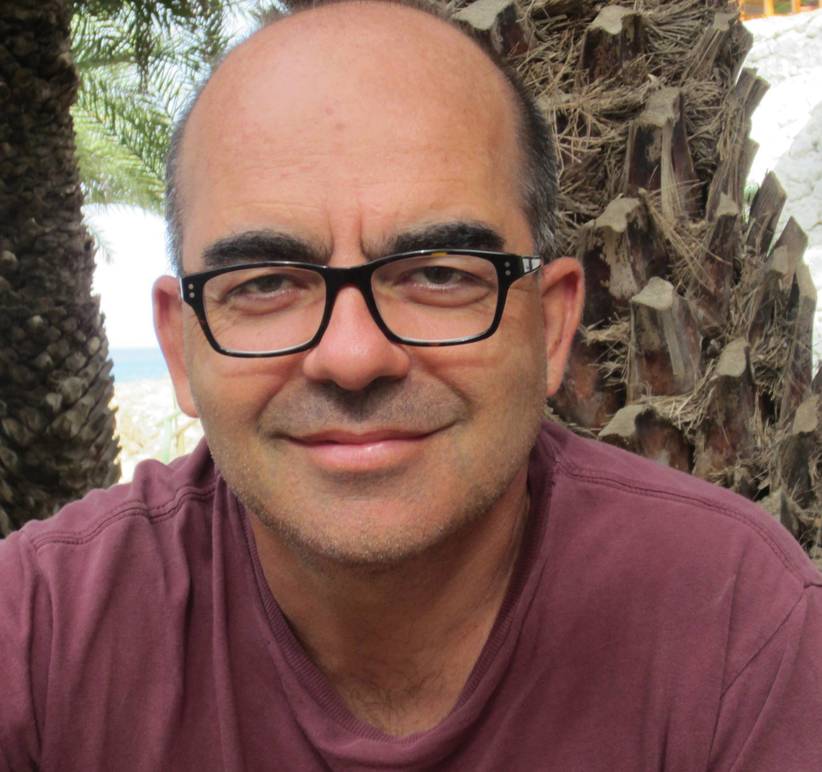

Author Nicola Gardini and translator Michael F. Moore met, after months of work and collaboration, at Casa Italiana Zerilli Marimò in a conversation about Gardini's novel Le Parole Perdute di Amelia Lynd (2012 Feltrinelli) and its English translation, completed by Moore, Lost Words (2016, New Directions).

Moderated by scholar Michael Wyatt, the conversation focused on Milan in the 1970s, coming ofage (including sexual awakening), the travails of translating and collaboration. The novel, winner of Casa’s own Zerilli-Marimò/City of Rome Prize and the Viareggio Prize “takes place on the cusp of an upheaval in Italian life. The 1970s in Italy may be best known for the clash between left- and right-wing extremists, but it was also a decade of social mobility, educational opportunity, and a sexual revolution. Lost Words captures a microcosm of this transformation in a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of Milan, littered with construction debris and tainted by the malice of petty gossip.

Viewed through the eyes of Chino, an impressionable thirteen-year-old boy whose mother is a doorwoman, the world contained within these walls is tiny, hypocritical, and mean-spirited. A new resident, Amelia Lynd, moves into his building and quickly becomes an unlikely companion to Chino. Ms. Lynd – and elderly, erudite British woman – nurtures his taste in literature, introduces him to the life of the mind, and offers a counterpoint to the only version of reality he’s known.”

“That was a historical period,” Gardini explained, “where high culture could meet low culture. I, like the boy in the novel, came from a proletariat family but I was no different from other kids my age who were coming from more well-to-do families. I had their same opportunity to attend a good university. Yet it was also a time of turmoil and of social preoccupation. I migrated to Milan from the South in those years and I grew up in an area very similar to the one described in the book, via Icaro, but despite that the book is not autobiographical. I don't have that many memories from that time but I see it as the beginning of the Berlusconi era, of an era where there was ambition to change the world.”

Michael Moore, also arrived in Milan, from Chicago, in the 1970s: 1975 to be exact. “I moved to Milan to attend Brera Academy of Fine Arts and I didn't know what I walked into. Schools were occupied, statues and other works of art were marked by a red A which meant Anarchy, protests were being held everywhere. It was not the Italy I was expecting.

Italy in the 1970s was living through its Years of Lead, a time of socio-political agitation that started in the late 1960s and continued into the early 1980s. The period was marked by a wave of terrorist attacks, protests, kidnappings and the birth of the Red Brigades, a revolutionary, paramilitary organization responsible for violent attempts to destabilize the country.

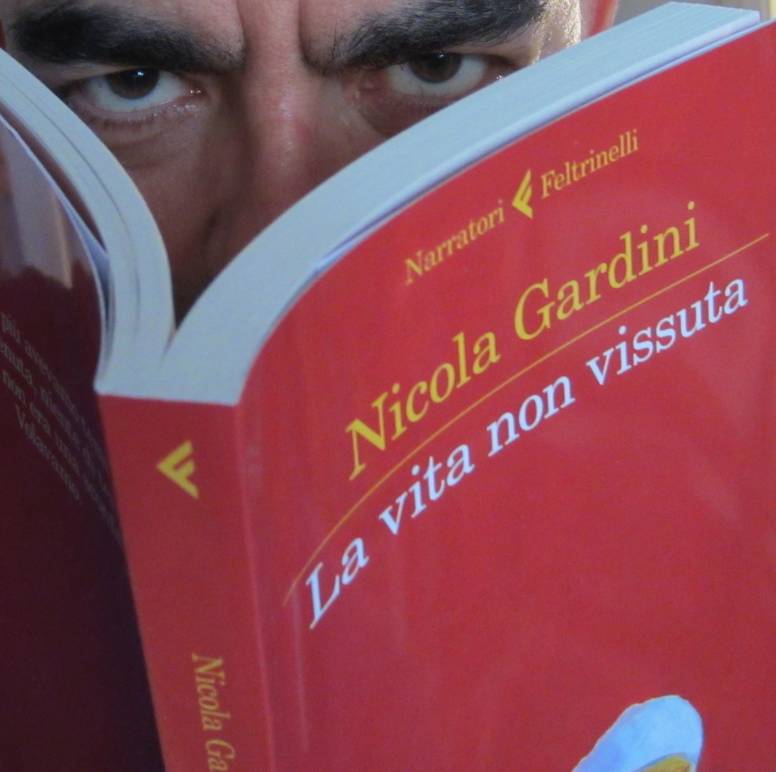

“Lost Words is not a historical book either,” Gardini added, “It's just a tale that happened to fit in those years. With this book I tried, through this specific story of a kid who grows up in a portineria (a porter's lodge), to instill faith in culture, in the value of literary knowledge and in the meaning of words.”

And words are not just what Michael Moore had to translate, a translation is so much more. For example, who knew it could be visual? Moore had a few films that helped him through it for their feel and their characterization.

“What's useful of translating the work of a living author is that you can ask him questions,” Moore joked, “But in reality I prefer to translate in private.” “I was not worried,” Gardini answered, “I trusted him completely and I believe that a translation is something completely new that has its own identity. It doesn't matter if it is different from the original, it cannot be the same just by the mere fact that the languages are different.”

Moore made some choices in the translation as leaving some words untranslated and getting rid of the Milanese dialect, which would be impossible to convey in English. In Milan people use the definite article before someone's first name: La Luisa or il Luigi, but saying The Luisa or The Luigi would be incorrect in English. “An American readership would not understand it,” Moore explained. He also had to chase down original quotes, from Shelley for example, that Amelia Lynd would spit out, but “because she often doesn't make sense, I distorted them too. That makes the translation more authentic.”

“I never worry that something might get lost in translation,” Gardini concluded, “because with something you lose there is always something else that you find. Something equally beautiful.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.