The modernist agenda challenging the parameters of what constitutes art was put to the test on December 22, 1942, when Alfred H. Barr, Jr. (1902-1981), the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, exhibited “Joe Milone’s Shoe Shine Stand” near the museum entrance at 11 West 53rd Street, Manhattan. This fascinating display was featured in The Christian Science Monitor, Corriere d’America, Harper’s Bazzar, New York Herald Tribune, The New York Times, Newsweek, Il Progresso Italo-Americano, Time, among other publications, my sources for this introductory post on the subject. Barr was quoted in several publications:

Joe Milone’s shoe-shine furniture is as festive as a Christmas tree, jubilant as a circus wagon. It is like a lavish wedding cake, a baroque shrine, or a super-juke box with no blank areas in the ornament. Yet it is purer, more personal and simple-hearted than any of these. We must respect the enthusiasm and devotion of the man who made it as much as we enjoy the result. Nearby in the Museum is an exhibition of Useful Objects Under 10 Dollars; but this a superbly useful object without price (“Joe Milone’s Shine-box On Exhibit In Museum,” Corriere d’America, December 27, 1942, p. 18).

Barr’s language, e.g., “purer,” “simple-hearted,” etc., points to his understanding of these unique objects. What exactly were these objects?

The set consists of a red-white-and-blue bar chair with a batik seat, a polish-box, complete with a factory-made aluminum footrest, an extra stand for the customer’s unemployed foot and a plush-covered stool . . . . (“Museum Shows Shoeshine Stool Without a Peer,” New York Herald Tribune, December 22, 1942, n.p.)

These mundane objects were transformed by the application of scores of "beads, billiard balls, bells, costume jewelry, a gilt cupid, ribbon rosettes, and innumerable other objects” purchased at “pushcarts and five-and-ten-cent stores” over the course of years (“Epic of Shoeshine Culture,” Newsweek, January 4, 1943, p. 64).

Every inch of the dazzling chair and its satellite objects is covered or hung with gleaming metal, with glass doorknobs and red, blue, silver, brass and iridescent buttons, ball and bells. On a shelf beneath the chair seat a gilt Cupid in a cummerbund of pearls plays a mandolin as he stands on a tambourine splendid with glass emeralds, topazes and rubies. Little iron flowers painted by Joe in pink, blue, orange and pimento are screwed into the throne-like base of the chair. Varicolored ribbon rosettes cover the seat of the stool. A long-tailed bird in brass is placed advantageously.

Delicate bathing beauties in Far Rockaway china sit on either side of the big shoe rest, while a china kitten wearing a necklace stands guards at the end.

The entire stand and it accessories repay careful scrutiny with endless discovery of new and minute objects, but the resplendent effect of the complete collection rewards even the most casual glance (“Joe Milone’s Shine-box On Exhibit In Museum,” Corriere d’America, December 27, 1942, p. 18).

Who created this fantastically ornate assemblage?

Joe (can we safely assume his name was Giuseppe?) Milone was born in Sicily (town unknown) circa 1887 (Encyclopedia of American Folk, 2003, p. 42) and emigrated to the United States in 1910. He lived at 10 Delancey Street, with his wife and son Accursio. Milone had wanted to be carpenter but had hurt his hand. He worked as a shirt presser in a laundry and shined shoes to make extra income at the corner of 7th Street and Broadway, near the Wanamaker’s department store. It was at the nonextant crossroad that Milone met sculptor Louise Nevelson (1899-1988), whose studio was nearby, several weeks before the late December exhibit at MoMA.

According to repeated accounts, Nevelson complimented Milone on his decorated shoeshine box and he replied, “It is the most beautiful shoe-shine box in New York City.” He then informed her he had another at home that he never used for work (Milone’s conscious transformation of a mundane, utilitarian object into a “useless” work of art, contradicts Barr’s read of the immigrant naïf) that was “the most beautiful shoe-shine stand in the world.” After visiting Milone at his Delancey Street apartment, Nevelson took the artistic bootblack and his creation to MoMA, showing it to museum curator Dorothy Miller who “found it remarkable” as did Barr. And so the exhibit, formally known as “Joe Milone’s Shoe Shine Stand” (MoMA exhibition #212), was mounted from December 22, 1942 to January 10, 1943.

The sculptor claimed that “This box is the symbol of our age, a thing and space that can never happen again. This is subconscious, surrealist art. It is an epic of Mediterranean culture” (“Epic of Shoeshine Culture,” Newsweek, January 4, 1943, p. 64).

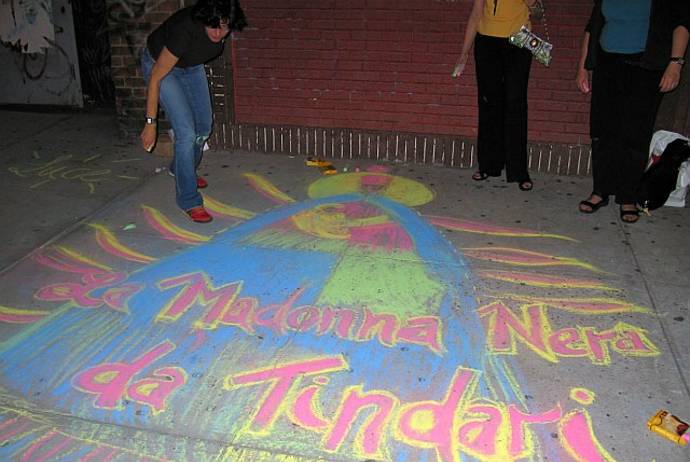

Sixty-six years later, we recognize the similarities with other examples of Italian-American traditional and self-taught artistic creations, from the glimmering strings of festa illuminations to the artisanal religious shrines crafted from wood framing and papier-mâché, and decorated with tinsel and gilded trimming, to the shimmering assemblages of Sabato Rodia’s Watts Towers and Litto Damonte’s Hubcap Ranch in California. The accrual method speaks to the encounter of Italian “arrangiarsi” and the detritus of American capitalism.

(left: Madonna dell'Assunta festa shrine, Little Italy, Manhattan, c. 1950; right: Our Lady of Mt. Carmel grotto, Staten Island. Photo: Larry Racioppo.)

Nevelson’s interpretation of Milone’s artistic work within the modern art frame was in sync with Barr’s perspective, which was informed by his “decidedly multicultural vision of modernism” (Helfenstein 2004, 46). It was under Barr’s direction that MoMA exhibited art by Latin American artists, African art (1935), the stone carvings of African-American William Edmondsen (1937), American folk art (1933 and 1938), Native American art (1941), and the religious folk art of the Hispanic Southwest (1943). It was this “belief in the pluralistic roots of the international movement of modernism” (Ibid., 47) that prompted the display of the Sicilian bootblack’s artistry.

Milone’s exhibited shoe-shine box (along with the exhibition of self-taught painter Morris Hirshfield in the summer of 1943) was cited by Steven Clark, chairman of the museum’s board of trustees, when he ousted Barr from his director position in October 1943. As Tom Patterson writes in his entry on Barr for the Encyclopedia of American Folk, “There were no further exhibitions of folk art or vernacular art at the museum during the last twenty-five years of Barr’s tenure [as advisor] there, nor have there been since” (p. 42).

According to journalist Lou Nappi of the Corriere d’America, Nevelson “predicted that Milone’s shoe-shine box would eventually win its proper place in art and that it had not already done so because its simple qualities which make it a masterpiece have failed to be recognized as yet.” It never quite did.

MoMA never purchased Milone’s quartet of encrusted pieces, much to curator Dorothy Miller’s chagrin. Milone is quoted as saying that his art was not for sale, “not even for a million dollars.” It is presumed lost.

It was Nevelson hope that: “Sometime, somewhere, somehow, somebody–if their (sic) sensitive enough–will find the right words with which to describe and analyze this magic thing.” This is my humble, first attempt.

(Thanks to LuLu LoLo and Stephanie Romeo.)

Bibliography

Josef Helfenstein, “From the Sidewalk to the Marketplace: Traylor, Edmondson, and the Modernist Impulse,” in Bill Traylor, William Edmondson and the Modernist Impulse. Josef Helfenstein and Roxanne Stanulis, Ed. (Champaign, Illinois, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2004), 45-67.