I was twenty-one when I arrived in Bologna in February 1977. I had no idea I was about to participate in a turbulent yet extraordinary moment in Italian history. Today there are books, web sites, and a feature film dedicated to what historians have simply come to call “The Movement of 1977.” For me, it was a deeply personal, life-defining experience.

The year before, I dropped out of Brooklyn College and was scrubbing pots in a restaurant, going nowhere fast. I didn’t have much to lose when first my Italian cousin Raffaele, with whom I drove cross country that summer and who was attending the University of Bologna, and then Claudia, a woman from Milan I had met in San Francisco, invited me to come to Italy. I had made enough money cleaning greasy pots to live in Italy for a year.

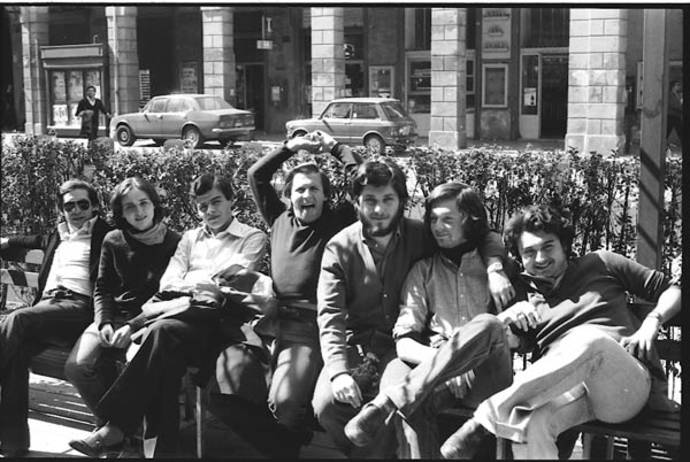

I had the good fortune of quickly falling in with a great group of left-leaning students of working-class backgrounds from different parts of the country. Valentino from Puglia, Giuseppe from Sicily, Danielle from the Veneto, Gianfranco from Sardgena, Vasco from the Trentino Alto Adige were a just few of my new friends. There was also Giuseppe from Umbria who went by the nickname “Humphrey Bogart,” and who repeated the Alberto Sordi line in English, “What’s a matter American boys?” from the film Un Americano a Roma.

Our meeting point was Piazza Verdi – where the rusting trio of modernist “totems” by sculptor Arnaldo Pomodoro’s stood somewhat incongruously – and, in particular, the Piccolo Bar. For one year, this was the center of my universe.

I ate full-course pranzi for 500 lire in the university cafeteria with everyone else. (I still have the bottle opener I pocketed as a keepsake.) It was in a crowded bar located on the corner of Via Zamboni and Via de' Castagnoli that I first encountered playwright Dario Fo and his satirical "Mistero Buffo" as we pressed together to watch his return to prime time television after being banned from the airwaves for fifteen years. I honed my Italian translating the songs of cantautore Francesco Guccini; “L’avvelenata” was my theme song that year. Endless political discussions, at a time when few Italians spoke English, also helped to improved my Italian.

By the time I arrived in the city, students had occupied parts of the university to demand school reform and to protest the lack of jobs available upon graduation. I joined my friends at political meetings held in various university buildings. I briefly broadcasted on the pirate radio station Radio Alice until a group of feminists ousted my cousin and me from the airwaves to discuss women’s issues. I marched in “autonomist” demonstrations, shouting the slogans of the day, from the puerile (“Schemi! Schemi!”) to that of the Paris student revolt of May 1968 (“Ce n’est qu’un début, continuons le combat!”/This is only the beginning, carry on the fight!). My parents were convinced they recognized me in a photograph of demonstrators published in a spring issue of Time magazine.

On March 11, 1977, in the city the Italian Communist Party had governed since 1945, the carabinieri shot an unarmed medical student, Francesco Lorusso, 25, during an autonomist demonstration. Pitched battles ensued between students and the police, with barricaded streets and Molotov cocktails used on one side, and tear gas and rubber bullets on the other side. Tanks rumbled down Via Rizzoli. French intellectuals Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, Felix Guattari, Jean-Paul Sartre, and others denounced the state’s repressive methods. In September, student groups forced the municipal government to sponsor a three-day, national conference against repression in the city, with free food and use of the sports stadium made available to the 100,000 people who came to Bologna.

I returned to the States at the end of the year having decided I wanted to study anthropology. The following summer I returned briefly to Bologna to discover the ebullient mood had evaporated. Members of the Red Brigade, a left-wing terrorist group, had kidnapped and killed former prime minister Aldo Moro. The tension was palpable. When I returned in 1982, I met with Humphrey, who worked in a bank on Via Zamboni, and Valentino, who was married, had a baby daughter, and was unemployed.

I also kept up with Enrico Franceschini. When we first met in 1977, Enrico was writing for a sports magazine. He was the only Italian I had come across who actually liked basketball and the way Americans spoke Italian. He moved to New York City in the 1980s and we hung out for awhile. I lent him my Italian-English dictionary, which I never saw again. We were even robbed together in Tompkins Square Park. As we lost touch, I followed his career as he became a journalist for La Repubblica, reporting from Jerusalem, Moscow, Washington, D.C., and currently London.

It was a pleasant surprise to come across Enrico’s book Avevo vent’anni: Storia di un collettivo studentesco, 1977-2007 (Feltrinelli, 2007) when I was in Italy two years ago. Enrico had sought out Valentino, Giuseppe, and other friends to ask what the experience of Bologna 1977 meant to them and what they have done since then. I was particularly moved by Humphrey’s description:

A Bologna bastava entrare in facoltà per essere quasi preso all’amo dai compagni del collettivo, che ti pescavano alle lezioni, in biblioteca, dal bidello o in corridoio. A me vennero quasi a cercarmi al bar di piazza Verdi, il Piccolo Bar. La vita era come una giostra, dalla mattina alla sera in piazza e poi nelle osterie. Un’ esperienza del tutto nuova per uno come me, venuto da una cittadina che era poco piu’ di un paese. Un nuovo modo di pensare. Una sorta di liberazione interiore. . . . (p. 88).

In Bologna, it was enough to enter in the department to be practically hooked by friends of the group, who would come get you during classes, in the library, have the porter find you, or in the hallway. They would almost know to come look for me at the Piccolo Bar in Piazza Verdi. Life was like a carousel, from morning to night in the piazza and then the tavern. It was an experience that was complexly new to me, because I had come from a small town that was little more than a village. A new way of thinking. A sort of interior liberation . . . .

In July 2007, I walked the streets of Bologna and wept uncontrollably. It wasn’t out of nostalgia for “quando eravamo giovanni e belli” or for “my Bologna” that had changed so drastically from my memories. I wept instead because I was overwhelmed by the sheer power of those times, by the intensity of the camaraderie, by the fervor of the political convictions, and by the dynamism of the creativity visible everywhere. Bologna 1977 was and remains a motivating force in my life.

After reading Enrico’s book, I dug out these photographs I made of my friends and others I met, the only images of mine that remain from that glorious year in Bologna. I post them in the hope that we might meet again, if only here, on the Net.

(Thank you Carmine Pizzirusso, Rodrigo Priano, and Stefano Messina.)