World Peace: The View From Israel. Tikkun Olam

“Peace and goodness,” Saint Francis used to say. “Shalom/Salaam” (peace) is the traditional Jewish and Arabic greeting. Roughly eight hundred years since he journeyed to the Middle East, Saint Francis’ message remains firm for its universal appeal, as do the region’s ties to Italy.

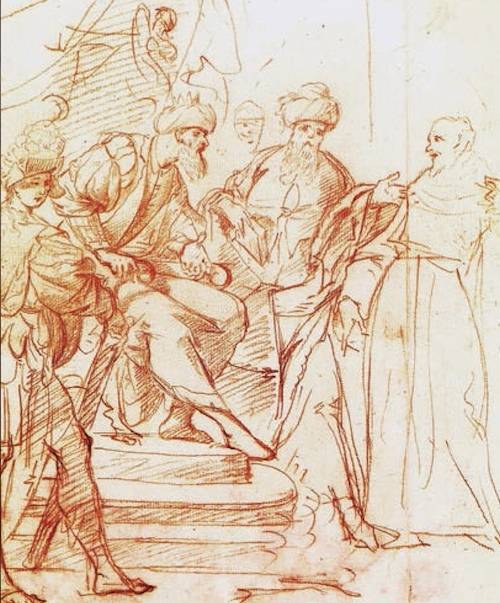

The gentle man of prayer was capable of courageous acts. Imagine what it meant back then to make the long trip across the Mediterranean to the Holy Land, then a war zone, and arrive in Egypt to meet the Sultan, a man of action, a revolutionary. In a time of radical conflict, Saint Francis became an ambassador of peace, not in the name of some abstract feeling but to make concrete and audacious steps toward peace.

He was not just a preacher but a builder of peace. The Franciscan message to “go and repair my house” means, I believe, that every one of us is obligated to work for peace and the world we live in. Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said as much last October 4th, the Day of Saint Francis, in Francis’ hometown of Assisi, when he outlined his plan to repair Italy. The Franciscan concept finds a counterpart in the Jewish concept of “Tikkun Olam,” to repair the world, a concept dear to to such secular statesmen as as the Nobel Peace Prize recipient Shimon Peres.

St. Francis in the Middle East

For eight centuries, ever since Saint Francis set foot in the Middle East, the presence of Franciscans has never waned. The Custodian of the Holy Land entrusted to the Franciscans and supported by the kings of Naples has kept the Christian heritage alive for believers and pilgrims from around the world without interruption for two centuries in the birthplace of Jesus and his creed.

And the first indispensable step of conserving paved the historic and humanitarian road for constructing. Modeling themselves after Francis, these envoys have become builders of peace—and therefore of bridges—and the pride they take in their own identity has lead them to respect the identity of others. This strong community stems from a common root: that of the Judeo-Christian culture which has played a decisive role in forging the European civilization we know today.

I find it interesting to think about this in Israel, a country whose existence hinges on its spiritual identity and thousand-year-old roots, yet at the same time a country characterized by an almost manic propensity for embracing innovation, for making scientific research a reality and economic boon. The country whose start-ups are founded in skyscrapers (better yet, in basements) is the same that faithfully remembers its desert roots, the nights spent under the frail shelter of huts, and honors the sacred scrolls discovered in the grottoes near the Dead Sea.

Is this the country of ora et labora? Ora et labora, Saint Benedict’s motto, that other great saint and forger of European culture. Here lies the intersection of Italian civilization—which has contributed so much (even to the language!)—the Patron Saint of our country, the multiform energies of European culture and the spirituality that spread out from the Middle East to the entire world in the form of monotheistic religions.

Leaving Jerusalem and Israel, the man who meets Saint Francis is reflected in the Saint, and wherever he is in the world, he seeks to become a messenger of peace. A peace that is indivisible, because, as the tragedy of the Shoah should have taught us, there exists only one race, the human one, and being brothers in a Franciscan spirit incites a spasmodic urge to make peace throughout the world. That urge is particularly felt between Rome and Jerusalem, the two cities that have represented the axis of action for the current Pope, who chose to take the name of the Saint of Assisi and has sought to bring together the Presidents of Israel and Palestine, Peres and Abbas.

The Mediterranean: A Place of Peace

Following in Saint Francis’ footsteps, a politician and man of faith named Giorgio La Pira founded the “Mediterranean Colloquies” in Florence, which, on October 4, 1958 (the Day of Saint Francis), kindled hope for a peace settlement between the Arabs and Israelis for the first time. Another commonality to emerge during the conference was that of the Mediterranean. The Mediterranean is a priority in the agenda of the Italian president of the European Union. It also provides a key to understanding Israel, a country whose identity hovers between Europe and the Middle East.

Rather than a space that divides different worlds, rather than an abyss for multitudes of desperate immigrants, the sea that Peter and Paul crossed on their voyage to Rome and martyrdom, and Saint Francis sailed in the opposite direction, can be a place that unites people, just as it united and enriched cultures long ago.

I am not referring to abstract symbols but concrete choices about our priorities, the essence of politics, for which—as President Renzi suggested on his visit to Tunis (a significant choice of destination for his first trip abroad as the head of the Italian government) last March—“the Mediterranean is not a boundary but the future of Europe and our countries,” a place of opportunity and hope.

This is a palpably Franciscan way of combating the culture of resignation, which hides behind the guise of realism (usually a convenient excuse for lazy inaction), and it signals a positive change, one based on a complementary demographic and intellectual relationship between the two shores evident in Israel and part of the Italian drive to make new developments.

Peace Can Be Built

Which is to say, building can take place. Even in places devastated by war, it’s possible to restore the church that the Italian Saint was called to repair, in the Hebrew spirit of “Tikkun Olam” and in the spirit of Saint Peter, the Jewish fisherman from the Sea of Galilee who laid the first brick of the Church of Christ.

This is not about utopian spirituality. The work of the Franciscans in the Holy Land, from Israel and Palestine to the places of martyrdom and suffering in Syria, is proof that service can be put to concrete ends. Take, for example, the educational institutions built in Acre, Jaffa and elsewhere, which I have visited. It’s beautiful to think that the Italian language is still remembered there. In my work, I have found the Franciscans to be great allies for spreading the Italian language.

I was greatly moved by my visit to the Custody of the Holy Land where the religious community still converses in Italian. Even when there are no Italians around, I heard people—priests from the Philippines, Mexico, Egypt—speaking my language, the language that Saint Francis helped build.

Thanks, Saint Francis.

Shalom, all.

*Italy's Ambassador to Israel

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.