Renzi Loses His Bet. But Now What?

Within hours of losing the constitutional referendum Sunday night, Matteo Renzi submitted his resignation as Premier, one of the few in Italian postwar history whose government lasted more than 1,000 days. Many had predicted that the referendum opponents would win, but by only a slim margin. No one had foreseen the stunning 70% turnout, or that, of these, only 40% would vote as Renzi had advised.

Almost all the commentators here agree that Renzi had made a grievous error for himself and his centrist and (occasionally) left-leaning government, with potentially destablizing consequences for Italy, with its feeble economy and troubled banks. A few pundits immediately dubbed the vote the "Renzit," as in Brexit, and the British daily Telegraph quoted "German business leaders" saying that the referendum defeat "threatens the very survival of the Euro."

However, the referendum was not about leaving Europe or the Euro; it was essentially a power struggle, one of the many in past decades. That struggle continues in the aftermath with talk of future national general elections. Both the M5S and Renzi himself are agitating for these to take place immediately, each attempting to take advantage of that respective 60% and 40% which they consider their own.

As many reasons to explain what happened are bruited about as there were voters. To start with the "no"'s, the most generous take the view that voters chose to honor the constitution promulgated at the bitter end of World War II, and which is proving remarkably solid. Others voting against the referendum objected to its central goal, abolition of the elective Senate, which would have limited powers vis à vis the Chamber of Deputies.

Others accused the referendum of concentrating too much power in the hands of the central government, of neglecting young people and neglecting the South. The cruelest comments came from the apparent victors, the Movimento Cinque Stelle headed by ex-comedian Beppe Grillo. The leaders of the M5S, or Five Star Movement, claim that the 60% of the vote was, loud and clear, against Renzi and his government's three years in office.

The "yes" voters are saying somewhat lamely that their 40% matches the size of the vote won three years ago by the Partito Democratico (PD), which Renzi still heads, at least for the time being. Others complain that the referendum, with its long and tedious list of tacked-on components, was simply incomprehensible. In fact, the daily Corriere della Sera felt the need to publish an entire book, written by lawyers and magistrates, to explain it -- which is not to say that anyone actually read that book.

The angriest of those who had hoped for a "yes" vote complain that Renzi made two gigantic and costly mistakes. First he insisted upon holding a referendum, whose victory he thought would be a piece of cake. Then he identified its presumed success with validation of himself. He mistakenly personalized the vote, even though at one point, realizing that he was heading toward an abyss, tried to back away from this identification.

A sober analysis of the vote comes from data assembled Dec. 5 by the Interior Ministry, the election observatory of the University of Urbino and polsters Demos and PI. A sharp North - South difference appears, with Renzi claiming 44% in the North but only 38% in the South. The self-employed provided the largest single bloc of "no"'s (76%), and pensioners the smallest (45%). Housewives (68%) and blue collar workers (66%) voted overwhelmingly "no," as did 61% of those between the ages of 18 and 29. Although this presumably reflects youthful anger at unemployment, particularly in the South, that has been a challenge neglected by governments for over twenty years.

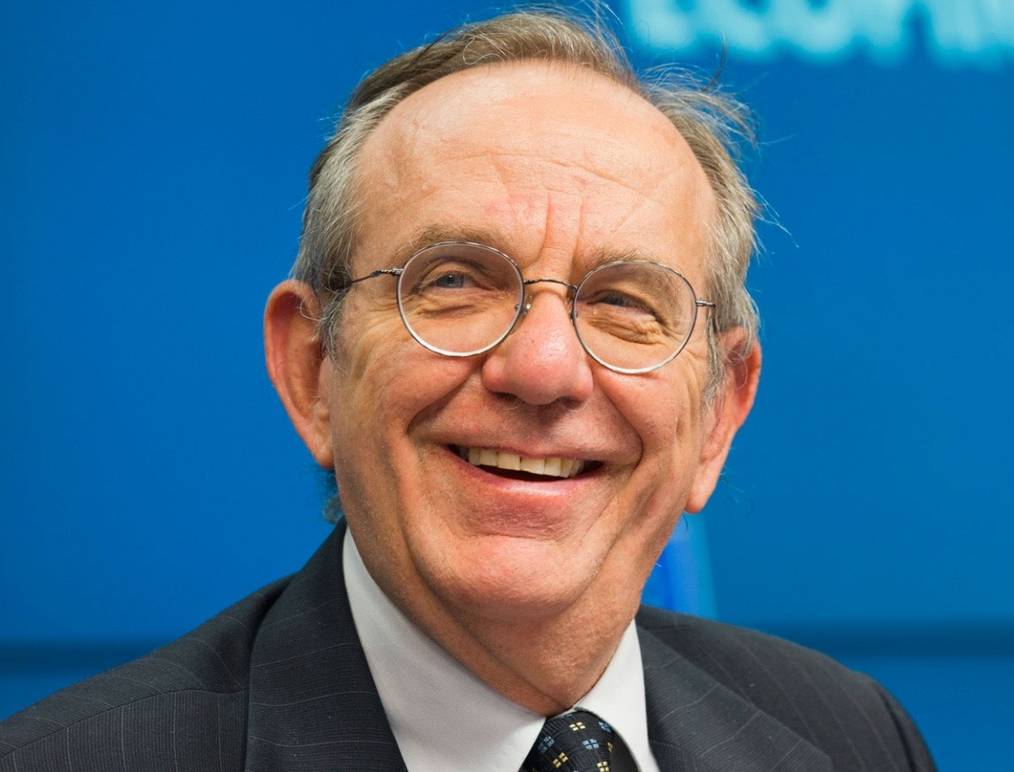

With victory, the M5S is demanding its turn at governing, but this is not a given. Ignoring Renzi's prompt resignation and weepy farewell, President Mattarella decreed that Renzi is to remain in office until a pending budget plan is passed. After that, Renzi appears unlikely to succeed himself, but the PD is not necessarily out of the game, and indeed possible candidates for a caretaker or, in the customary phrase here, "technical" government, come from his own party and cabinet. Among those mentioned are the respected Pier Carlo Padoan, Minister of Finance and the Economy, and Dario Franceschini, Culture Minister.

There is also sharp disagreement, including within the PD, over the wisdom of holding national general elections immediately, as both Renzi and Grillo urge. In addition, the quarrel among the parties over the method of voting endures. The so-called "Italicum" reform voting law was passed in Parliament but does not apply to the Senate. Calling new elections is the responsibility of the President, and the suspicion is that President Sergio Mattarella is resisting pressures for elections. The President of the Republic cannot dismiss Parliament and call for political elections before that law is amended or a new law is approved.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.