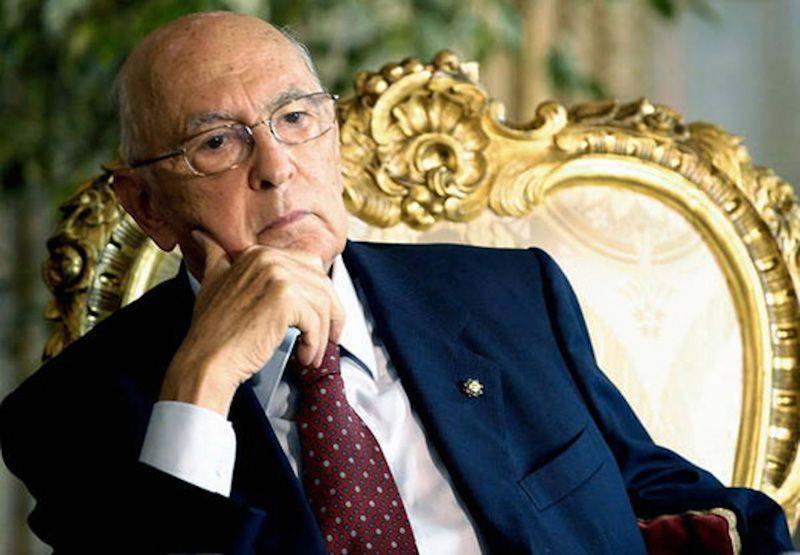

Napolitano Has the Last Word, for Now...

ROME - It is unlikely that we shall ever know the full story, but it is nevertheless clear that, through careful mediation, President Giorgio Napolitano has succeeded in calming at least some of the troubled waters of political Italy. This is a victory for stability, for Italy, for justice, for Premier Enrico Letta's coalition government, but also for the moderates within former Premier Silvio Berlusconi's splintered Freedom Party (PdL), who have been counselling a cautious approach even as an obviously fraught Berlusconi himself launches a new party.

The feisty PdL hawks like Daniela Santanche have been more or less openly threatening to bring down Letta's coalition government, of which Berlusconi's party is a fundamental part, unless Napolitano would grant an amnesty to liberate Berlusconi from the political consequences of his high court conviction for tax dodging. The hawks' argument has been that Berlusconi is a politician representing "ten million voters"--in fact, something like eight million--and therefore cannot, this being a democracy, be shunted out of political life by magistrates who are (from their point of view) overly politicized.

In fact, the laws governing the situation are themselves slightly ambiguous, and the daily La Repubblica this week published, facing each other, two entirely differing versions of Berlusconi's legal right to continue in political life or to be legally excluded. Each was written by a prestigious, experienced justice. Lending credence to the PdL protests was an ill-considered, apparently gossipy telephone interview given last week by the chief presiding justice of the Cassations Court, Antonio Esposito, to a reporter from the daily Il Mattino of Naples.

Up to that point his court was basking in praise for its upholding the principle that all citizens are equal before the law. The recorded text of the interview, given prior to official publication of the sentence and its legal basis, has yet to be published, but news reports accuse Judge Esposito of revealing that the conviction was justified because Berlusconi "knew all about" the multi-million-dollar tax scam; Berlusconi's defense has been in part that he was too occupied with political affairs to know about the tax dodge scheme involving overseas acquisitions of film rights for Berlusconi's media company, Mediaset.

If nothing else, a presiding justice's conceding any interview to any reporter is, to say the least, almost inexplicable. But in addition Esposito supposedly also jokingly discussed what phone taps had revealed about Berlusconi's sex life. True? Not necessarily. By one account there were no salacious descriptions whatsoever. Another version has the "interview," to the extent that it was such, spoken in such a thick Neapolitan dialect that the later listeners had trouble deciphering the words. The matter is now passing into the hands of the high council of magistrates, where Esposito risks being found guilty of misconduct.

This emergency coalition which has right and left sharing power has been dubbed the "accidental government." Not surprisingly, the man holding its reins, Premier Letta, has been on pins and needles while awaiting a resolution to the problems raised by Berlusconi's conviction and his defenders' appeals to Napolitano. To save the government, would the President, could he legally, grant Berlusconi the amnesty being claimed by the PdL hawks? At the same time, some in Letta's own left-leaning Partito Democratico (PD) feared that Berlusconi would opt to go to prison so as to play the victim. Already some newspapers were comparing him with, of all people, the imprisoned Nelson Mandela.

Napolitano's cautious and marvelously ambiguous decision came in a note issued August 13 from the Quirinal Palace, launching an avalanche of various (and sometimes conflicting) interpretations. The best synthesis came in a tweet by PD Senator Corradino Mineo, former head of RAI News 24: "Here's what I understand from [Napolitano's] statement: 'I'd like to [grant the] amnesty but can't. B's political role is essential but his sentence must be respected. Amnesty? They have to ask for it first.'" Most importantly, an amnesty is unlikely, if not ruled out yet, but Berlusconi still has the possibility of remaining in political life. What Mineo may have forgotten to say was the Napolitano also categorically excluded Berlusconi from the risk of imprisonment, while leaving open that he will likely remain under house arrest or--Heaven knows doing what--in the redemptive hands of social workers.

But the problems for Berlusconi do not end here. The PdL is in its last gasps, slated to be replaced by a renovated Forza Italia, and its organizers' plans were to have airplanes, among other things, flying over Italian beaches this Ferragosto holiday August 15 with banners bearing the reborn party's name. Should that money be spent? Is it too early? For others in his party the essential problem is that they have no single leader who comes anywhere near to attracting voters as Berlusconi does. Unlike the no less troubled PD, the PdL, or Forza Italia, has no attractive alternative leader, no Matteo Renzi waiting in the wings. Without Berlusconi as their leader, there would simply be no conservative party whatsoever. Even Berlusconi's daughter, Marina, 48, who had been touted as his logical successor, has just bowed out.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.