Mafiaman…Could This Be the End?

I had the opportunity a few years ago to meet Ernest Borgnine, the actor who played Joe Petrosino in the 1960 film Pay or Die, but who’s perhaps better known through his previous film appearances in From Here to Eternity and Marty, and the McHale’s Navy television series. I was curious if he had ever been tempted to play a gangster in a film. He told me that he was offered the part of Al Capone in the gangster’s 1959 biopic in which starred Rod Steiger, but he turned it down. When I asked him why he turned it down he told an amusing story about how when he was a child his mother used to threaten bad behavior with the warning that Al Capone was going to get him if he wasn’t a good boy. “That guy frightened me pretty badly, so much so that I couldn’t even play him in a movie,” he replied.

That was the only time Borgnine remembered being offered a role as Mafiaman. There weren’t many Italian gangster films made by Hollywood in the prime of Borgnine’s acting career, that period after the 1930s when Hollywood censorship had put a lid on many of the gangster film

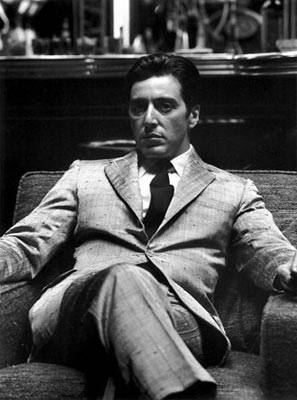

possibilities. It wouldn’t be until Puzo and Coppola’s The Godfather (1972) that the Italian gangster was realized as a sure draw to the box office, and a sure pain in the collective Italian American consciousness and culo. So what was it that made this Italian gangster figure so popular? Two things: timing and talent.

First of all, the gangster figure emerges in American popular culture at the time when the United States is shifting from an agrarian to an industrial based economy, so people are moving away from the farms and into the cities; this was also a time when immigration to the United States was at its highest and xenophobia was rampant. These became the right ingredients for setting up the Italian American man as the gangster, even though “Mafia man” had yet to rise to his ultimate status in real life.

Easier access to stylish consumption, through fancy dress and flashy cars blurred the earlier lines that separated social class. As street criminals began associating with the upper echelons of society, it became harder to tell the gangster from the corporate elite. This enabled the criminal to more closely resemble those in the rising business class, and for the sake of film (not to mention the good name of film investors), the gangster would have to be coded in order to maintain that separation between the “American” business man and the criminal; the cinema criminal then is rising in class and assimilating to mainstream culture at the same time American urban ghetto white ethnics are trying to do the same, and so if you code the gangster as ethnic, people won’t confuse him with the real criminals of the newly burgeoning economy.

Just as the gangster came to represent America's attempts to struggle with the advent of image-driven consumption, the gangster also represents traditional male aggressiveness and its use as a means of controlling his world. Nowhere was this more obvious, writes Ruth, than in the representation of the gangsters' treatment of women. A defender of "conservative gender values" on the one hand, the gangster also depicted an "openly expressive sexuality” that was becoming more acceptable in urban life. The prototype for this gangster, says Ruth, is none other than Al Capone, what he calls an "attractive and repulsive" figure that

"illuminated the lives of urban Americans." And when you look at the actors who have played Capone, his cronies or his descendants, you find an incredible pool of cinematic talent. Capone’s wannabes have lined up in real and Hollywood history so we can trace a line all the way through to Tony Soprano. But there’s more to the gangster than his Italian good looks and his fortuitous appearance in the right place at the right time.

Film scholar Jonathan Munby wrote that the gangster provides us with a view into our world from a different perspective: “If there is a problem the society is worried about or a fantasy it is ready to support, odds are it can be located in the gangster”. As Jack Shadoian points out in his study of gangster films entitled Dreams and Dead Ends the gangster embodies “Two fundamental and opposing American ideologies—a contradiction in thought between America as a land of opportunity and the vision of a classless, democratic society”. The gangster then functions as the scapegoat for the obsessive desire for self-advancement, and unrelieved class conflicts are played out in films. He becomes, for the United States, the only sanctioned soldier in the class war; and ultimately he teaches us that it is a losing battle.

In spite of all this scholarly work, people don’t associate the typical gangster with anything but the Italian American male: Mafia Man, constructed by non-Italians, was refined by Italian American writers and filmmakers, and then imitated ad nauseum. But what’s stronger the facts or the fiction about Italian/American gangsters?

The Sopranos continued to milk the myth, popularized by Puzo, that organized crime is monopolized by Italian Americans. If Puzo admitted that much in The Godfather was made up, then why do Italian Americans wince when Hollywood sends out another formulaic gangster film? Why should fiction be so upsetting?

The answer lies in the fact that for nearly seventy-five years Mafiaman has been Italian/American culture in the eyes of America’s filmgoers. In spite of some recent books, the regrettable truth is that the fictional Mafiaman is stronger than the facts, and the facts of Italian/American history will never be as attractive as the fictional myths. We know that the gangster figure meets a fundamental need by allowing Americans to reclaim a sense of power in a society gone out of control. But as these recent publications prove, the mafia has been a convenient and relatively safe dragon for American heroes to chase.

In the meantime more terrible monsters terrorize the American way. And as long as the U.S. has Mafiaman, we don’t have to admit that we are failing in the real fight to make America a safe and healthy place to live.

So what’s next? Is there room for a reinvention of Mafiaman? Will Italian American culture develop to the point where Mafiaman will be buried for good? Up until this point, Italian America has been often defined by the myth of mafia, but in the face of contrary evidence, what we do in response to the myth of Mafiaman will define us and determine the future of our community and identity as Italian Americans. If we seriously invest in education and the arts we this could be the end of Mafiaman, and the beginning of a renaissance of Italian American culture.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.