Early Elections Loom - But So Do Gloomy Warnings

Amid a chorus of warnings, national general elections are almost certain to take place this autumn, six months before the slated end of the legislature. Behind the demand for a general reckoning are three powerful forces: former Premier Matteo Renzi's Partito Democratico (PD), Beppe Grillo's Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S) and Silvio Berlusconi's reborn Forza Italia, with a further push from Matteo Salvini's Northern League.

Each has its reasons for lobbying for early elections. Renzi's party commanded almost 41% of the vote in the European elections of 2014, but has lost ground ever since. When Renzi foolishly called a nationwide referendum on a proposed a constitutional reform he had expected to win last year, with 65% of Italians participating, he was trounced, 59% to 41%. That defeat precipitated his resignation in December 2016 and replacement by today's Premier Paolo Gentiloni.

Further weakening Renzi's PD was the recent defection of his party's left wing under Pier Luigi Bersani. Polls conducted in late April gave Bersani's new mini-party, Movimento dei Democratici e Progressisti (MdP), perhaps 4% of future voters, and the PD reduced to under 27% -- hence Renzi's plea for a quick national vote that might curb further PD losses.

Renzi's loss was the gain of what is now being called "Grillism." Beppe Grillo's M5S has steadily forged ahead of the PD, currently reaching some 27%, according to an EMG poll measuring "intentions to vote." Alligned with Renzi and Grillo is Berlusconi's renovated Forza Italia, which EMG estimates at copping around 13% of the vote.

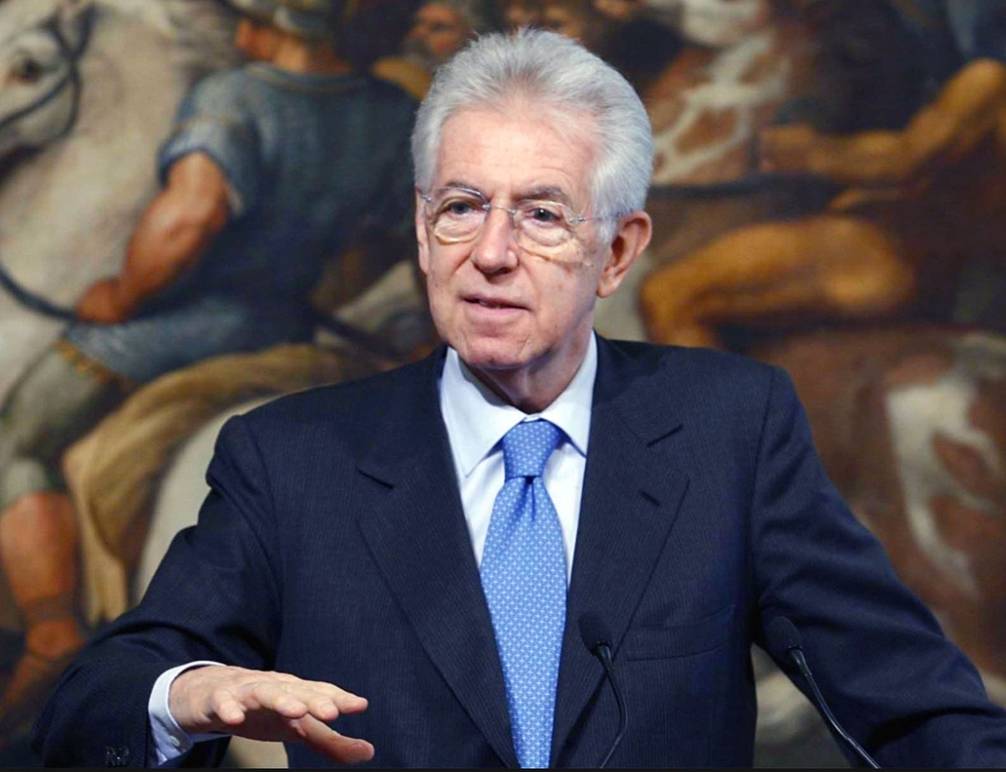

The battle for early elections is not yet won, nevertheless. New elections bring the risk of a possibly chaotic future for the government, plus leave a host of unfinished bills in Parliament. "Renzi is putting personal power before the interests of the country," thundered Mario Monti, senator and former premier, on May 31.

The problems begin with writing a new law governing the rules for voting, just now in a tumultuous marathon session under debate in Parliament. In essence, two alternate versions are being considered: majority versus proportional rule. In the majority vote, or first past the post, the winner takes all; as presently written, if that winner gains over 40% of the vote, the party takes 55% of the seats in Parliament.

The more likely outcome is a return to the former proportional system, in which each party wins the exact percentage in Parliament (Chamber of Deputies and the Senate) as earned in the polls. Here the weak point is that the system obliges the winners to form coalitions that are not necessarily easy to create or to manage. For Valerio Onida, former president of the Constitutional Court, however, this is not a defect: "The logic of forming a coalition, inherent in the proportional vote, reflects today's Italian political reality as well as voters' orientation."

The proposed new voting law, Renzi style, would eliminate any party (or force it into wobbly coalitions) that failed to earn 5% of the vote. Those most antagonzied by this possibility include the moderately rightwing Alternativa Popolare (AN), which was created only last March 18 and is headed by Angelino Alfano, angry because until now his party has served as Renzi's prop in the present coalition government.

Given the uncertainties, numerous serious commentators are begging for the big parties to slow down. The gloomiest prediction is that the proposed early elections will lead only to months wasted in trying, without success, to create a new coalition government, with months wasted until a second national general election has to be scheduled in the end. Opponents also point out that these past five years have been particularly unproductive. Not least, unfinished projects are crowded onto the Parliamentary agenda, beginning with the budget bill.

At the moment, Renzi and Berlusconi are projecting a coalition together, sarcastically dubbed "Renziconi-ism." Such an alliance with Berlusconi would obviously antagonize those PD voters who had originally signed onto what they thought would be a Social Democratic party.

There are alternatives to Berlusconi: Renzi could seek to work together with such relative national newcomers as the much admired former Milan mayor Stefano Parisi, who has just created his own new party, Energie per l'Italia. In theory, other small moderate groups, including even Alfano's newly minted Alternativa Popolare (AP) could make common cause with Renzi's PD.

Alligned against a "Renziconi" solution are Grillo along with populist leader Salvini, an admirer of Marine Le Pen. Salvini's Lega Nord party (which has long since gone national) now commands perhaps 12.5% in a potential election. If the polls are right, together these two could have almost 40% of the vote. However, Grillo's supporters are loners, and this may prohibit these two from joining forces.

New elections would mean tearing up a host of important bills, besides the crucial budget, pending before Parliament. One, dubbed the Anti-Mafia Code, would permit the seizure of property illicitly gained through corruption. Others are a reform of the statute of limitations; a law permitting a patient the right to refuse medical care at the end of his life; another granting citizenship to immigrants' children born or raised in Italy; legalization of cannabis for personal use; and, lastly, a law making torture a criminal offense (!)

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.