Far from Mulberry Street

“California is not what people generally think of when they think about the Italian immigrant experience,” remarked Suma Kurien after a screening of Finding the Mother Lode, the new documentary she produced and wrote with her husband, Gianfranco Norelli, who also directed.

The filmmakers presented and discussed their latest work, which will be aired as a three-part miniseries on the Public Broadcasting System in February, at a December 15 event at New York University’s Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò.

The documentary is a companion piece to their acclaimed 2007 film, Pane Amaro, which portrayed the Italian immigrant experience on the East Coast.

Kurien said that when they showed Pane Amaro to Italian American Californians, they said, “Great film. But it’s not our story."

Intrigued, the filmmakers decided that their next work would tell that lesser-known story of Italian immigrant experience in California, which markedly differs from the more familiar East Coast narrative. The result of three years’ research – and sixty hours of filming – is an engrossing, revealing, and beautifully made work. Finding the Mother Lode eschews the clichés of ethnic documentaries (the triumphalist narrative of immigrants achieving the “American Dream” and the focus on outstanding individuals, usually men) to provide a more complex account of the California immigrant experience.

Purchase the DVD online from Amazon.com

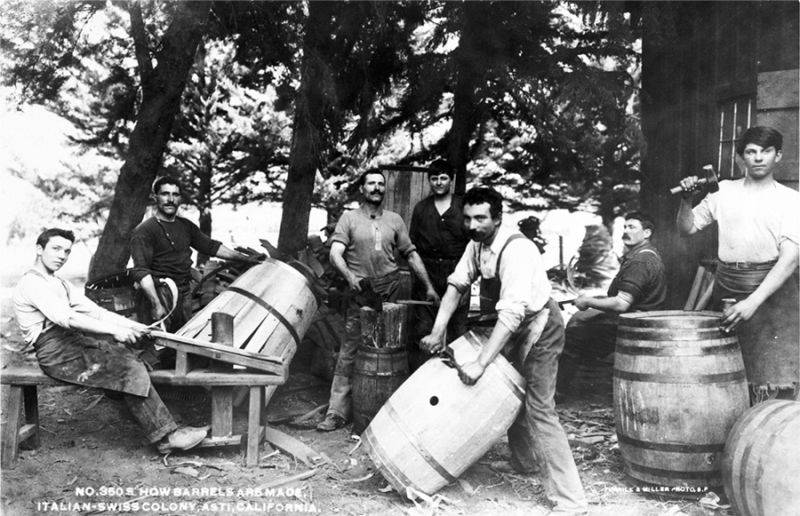

Prominenti do appear in the film. They include Amadeo Giannini, the California-born son of immigrants who founded the Bank of Italy, later the Bank of America; Andrea Sbarbaro and Pietro Carlo Rossi, the founder and director of the Italian Swiss Colony winery; and newspaper publisher Ettore Patrizi, who paid dearly for his ardent support of Mussolini’s Fascist dictatorship. Joe di Maggio also makes a brief appearance.

But the filmmakers wisely concentrate on how the immigrants achieved remarkable economic and social mobility in the Golden State, using the skills and experience they brought with them from Italy, and how their status as white Europeans fostered their assimilation. The film’s exploration of the Italian experience in California moves from Sutter Creek to San Francisco, to Stockton, Monterey, San Diego, and Los Angeles.

Italians first came to California in large numbers during the Gold Rush of 1849-1850. Most who tried to find gold did not succeed, and they instead became farmers, fishermen, bankers, lumberjacks, winemakers, construction workers, merchants, and entrepreneurs.

Unlike the majority of Italian immigrants to the East Coast, who came from Italy’s south, the earliest immigrants to California came from northern regions, mainly Tuscany and Liguria. (One of the film’s interviewees jokes that a “mixed marriage” meant one between a Tuscan and a Ligurian.) They generally had higher rates of literacy and were more skilled. Many of them – more than forty percent – chose to settle in rural areas, whereas only about eight percent of East Coast immigrants did so. They hastened to become naturalized citizens so that they could own land in northern California, where the climate was similar to that of the places they had left.

In Pane Amaro, Norelli and Kurien depicted the discrimination southern Italian immigrants faced when they arrived. But the northern Italians who constituted the majority of the early arrivals to California generally were welcomed by the native, Anglo-Saxon population. They enjoyed white privilege – unlike Chinese or Mexicans, they could own land. Moreover, some practiced discrimination against other immigrants – the Italian Swiss Colony winery refused to hire Chinese workers.

But Finding the Mother Lode highlights two historical incidents that demonstrated that the snake of anti-Italian prejudice lurked even in sunny California, the state that folksinger Woody Guthrie described as a “garden of Eden.”

In 1909, Italian immigrant workers at the McCloud River Lumber Company went on strike to protest wage cuts and discriminatory practices by the company’s mangers, including segregated housing in the lumber camps and higher prices in the company store. Although they made up two-thirds of the McCloud workforce, the Italians were subjected to repeated slights, insults, and abuses from other workers. The two-week strike ended when Governor J.N. Gillet sent in the California National Guard to break it – the first such occurrence in the United States.

Norelli, during the discussion after the Casa Italia screening, noted that the McCloud strikers were immigrants from northern and southern Italy (Calabria and Sicily). He said the company tried to exacerbate divisions between the two groups, even offering “white” status to the northerners if they would end the strike and return to work. Instead, as Norelli noted, “The northern and southern workers stuck together, as they did in other strikes,” such as the 1913 strike by textile workers in Paterson, New Jersey.

During the World War II era, Italians in California came under scrutiny as potential “enemy aliens” – even San Francisco’s American-born mayor Angelo Rossi was considered suspect. In 1942, some 1,800 Italian-born Californians were taken into custody and detained under wartime restrictions; others were relocated outside California. Their fate, however, was far less harsh than that of Japanese Americans. Unlike the Italians, who were deemed “enemy aliens” for only nine months and who were mostly non-naturalized California residents, the Japanese – some 120,000, most of them U.S. citizens – were forcibly relocated to internment camps for the duration of the war, losing their homes and livelihoods.

Finding the Mother Lode presents two types of ethnic consciousness, one epitomized by those immigrants (and their descendants) who, seeking to preserve and transmit their culture, married only their paesani/paesane. Another, more expansive ethnicity is embodied in the figure of Sabato “Simon” Rodia, an immigrant laborer from Campania who, working for more than thirty years, built the Watts Towers – seventeen interconnected sculpture-like structures, the tallest reaching nearly 100 feet, in the eponymous, working class Los Angeles neighborhood populated mainly by African Americans, Latinos and Asians. Rodia called his masterwork – which has been designated a National Historical Landmark – “Nuestro Pueblo” (“Our Town”). His Spanish-named installation is decorated with found objects and designs reflecting various cultures; one of the towers, the "ship of Marco Polo,” has a twenty-eight-foot spire.

Suma Kurien remarked that while planning Finding the Mother Lode, she and Gianfranco Norelli wanted to “explore how one lives in a multiethnic, multicultural society and maintains one’s culture.” Some, Kurien said, did this by marrying only other Italians. Sabato Rodia, she said, “was able to hold on to his Italian identity and heritage in the midst of a very multiethnic community, to be a part of that community, and build a ‘nuestro pueblo’ with a place for everyone.”

Kurien – born in India, raised in Africa, and a New Yorker for decades, the partner and collaborator of an Italian immigrant, and a fluent speaker of Italian – said that Rodia’s way “certainly speaks to me.”

PBS will broadcast Finding the Mother Lode in three, thirty-minute segments in February 2015. Check local station listings for details.

The full-length, 104-minute version of Finding the Mother Lode is available on DVD from Amazon.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.