Anti-Semitism in the United States: When and Why

Last week we reflected so thoroughly on the question of Jewish persecution during Fascism, that we seemed to forget that Italy was and is not the only anti-Semitic country in the world. Not by a long shot. Even the United States, commonly considered a “melting pot” essentially composed of liberal and welcoming people, has its share of prejudice against Jews.

The Italian Academy at Columbia University was the only institution that invited us to focus on this particular issue. Ira Katznelson, Ruggles Professor of Political Science and History at Columbia, held a symposium based on the essay “The Liberal Alternative: Jews in the United States during the Decades of Italian Fascism”.

The audience, various and heterogeneous, was mostly American and almost surprisingly included people of all ages: young people to senior citizens were all interested in discovering an original perspective, by which—as so rarely happens—Americans were the ones being judged by history.

With them a number of well-known guests who had already participated in the week’s events were present: Natalia Indrimi, Andrea Fiano and Stella Levi, respectively Director, Chairman and member of the Board of the Primo Levi Center; and the Consul General of Italy in New York Francesco Maria Talò.

In the warm, elegant library situated on the third floor, Professor Ira Katznelson, introduced by the Acting Director of the Italian Academy Barbara Faedda, promptly stated, that Americans also harbored a sometimes-deep discomfort toward Jews. “In considering the years from the 1920s to the Second World War, my purpose – speaking as a historian – is to understand this history not retrospectively but prospectively. How did things look after time? What attitudes, circumstances made the Jews’ condition in America seem more uncertain than it later proved to have been?”

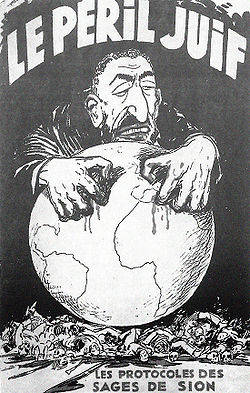

Supported by a wide range of documents, press articles and testimonies from the time, he explained that Jews felt marginalized even before the 1922 Fascist march in Rome, when they were wondering how to preserve their traditions and values in a country that seemed “indifferent and sometimes hostile to them”. Shortly after World War I, he continued, discrimination against Jews grew, especially in the academic field where the influx of Jewish students was viewed with animosity. In 1936 an editorial in Fortune Magazine reported that Jews were considered one of the causes of the Great Depression, draining American finances with their conquest of the most powerful economic institutions in the country: “they monopolized the opportunities for economic advance”.

In reality, historical surveys demonstrate that this is entirely erroneous: Jews played only a fractional role in this field, controlling a small percentage of companies and financial institutions, and were completely absent from heavy industry sectors such as aviation, petrol and automobile manufacturing. Thus, once again, xenophobia was unjustified.

Still the popular perception was that Jews were interested in economic advantage, as part of their non-Christian heritage. About 45% of the American population, according to surveys, felt deep “skepticism” toward them, a sentiment that was destined to affect American foreign policy during the 1940s. In fact, at first the U.S. passively stood by while European Jews were massacred and persecuted by the Fascist and Nazi regimes. Only with President Truman, who was primarily concerned with the country’s bilateral relations with the Soviet Union, did the “Jewish question” become a priority in the State Department’s agenda. The arrival of thousands of refugees from Europe coincided with new accusations: “They were said to be angry at American money and the ‘liberal alternative’ offered in their new country.”

It was actually this “alternative”, the professor concluded, that allowed Jews to enhance their social and economic position in America, especially from the 1970s on. Democracy demands, in fact, a constant application of the principles of fraternity and solidarity among people of different races, social extractions and religions. The “liberal alternative” was to become the primary source of contemporary American Jewish nationalism.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.