Still Deep in Shock, Genoa Soldiers On

ROME -- Still deep in shock from the tragic collapse of the Morandi Bridge, causing the deaths of at least 43 people, Genoa nevertheless is soldiering on. "The city has the intelligence to improve itself and to learn how to prevent such disasters in the future," said architect Renzo Piano in an interview August 14, shortly after the collapse. Piano, a native of Genoa, is world renowned for designing the Whitney Museum in New York, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Shard skyscraper in London.

A peculiarity of this hard-working industrial city, which boasts the busiest port on the Tyrrhenian Sea, is its geological structure. "Genoa is vertical, rocky, steep, and with deep tempestuous waters," Piano pointed out. In fact, tucked between sea and a steep ridge of mountains, the inhabited area of the central city, founded in the 5th Century BCE, is fairly narrow, which means that the population density there is acute. And that is why the killer bridge, which crossed directly over apartment blocks to connect the two far ends of Genoa, loomed so important when it was built in the Sixties.

So now what? No one has ever accused the Genovesi of being less than industrious, and the locals, from Mayor Marco Bucci to ordinary citizens, must look ahead to build a viable future for themselves and for their children. Because the collapse of the bridge cut the city in two, subways are being kept open until 1 am, and 42 extra train links have been provided, along with free bus service from Bolzaneto and Rivarolo to Brin.

"A new road artery reserved to the big trucks will open soon," Mayor Bucci says. "I see a strong will to react, from the people in the factories who have fought to offer us machinery and cranes. The other night the electricity company Ansaldo sent a giant turbine to help out under the bridge. There is the will to react: we have had to face an enormous drama, but we shall give it our best effort. We lost four traffic lanes but will build five."

A few months ago Enrico Musso, professor at the Department of the Economy of Transportation at Genoa University and a former senator, presented a transportation project that called for new streetcars, more train station stops, advanced connections from airport to town and more links via water. At the time many put down his proposal as a daydream. Now it is being incorporated into a broader proposal on sustainable transport for Genoa, being presented to Mayor Bucci on August 23. Already, plans for a new steel bridge are already being drawn up.

First, however, the entire broken bridge must be torn down and its huge cement components removed as soon as possible. To do so, the homes of those beneath the bridge will have to be torn down, which means that housing and appropriate funding for their inhabitants must be arranged quickly.

The Genovesi called the Morandi Bridge their Brooklyn Bridge. The flaws behind the collapse are still being studied by technicians, but at the moment three stand out. First, the steel rods seem to have withered inside their handsome cement casing. Secondly, the techniques utilized to measure the soundness of those rods were outmoded, sometimes simply by tapping a hammer. Third (and this is debated), no one in the Sixties imagine the amount of future stress that would result from the heavily loaded, gigantic trucks passing through Genoa from its port to the rest of Italy.

The concerns over the collapse have rung alarm bells elsewhere, for, "This could have happened to any of us," said Christophe Berti, editor-in-chief of Le Soir. "The collapse is surely the symbol of an aging Europe, which is losing its image of development and modernity it had back in the Sixties. The tragedy could have struck Belgium, France and any other nation in Europe." Or in the U.S.; as one example, at Fairview Park in the industrial area of Cuyahoga Country a bulky, multi-span bridge has had to be closed and risks demolition. Nearby in Cleveland is the Central Furnaces Bridge, whose western approach has had to be removed, leaving it a bridge to nowhere. And the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Bridge, built in 1956, has been abandoned.

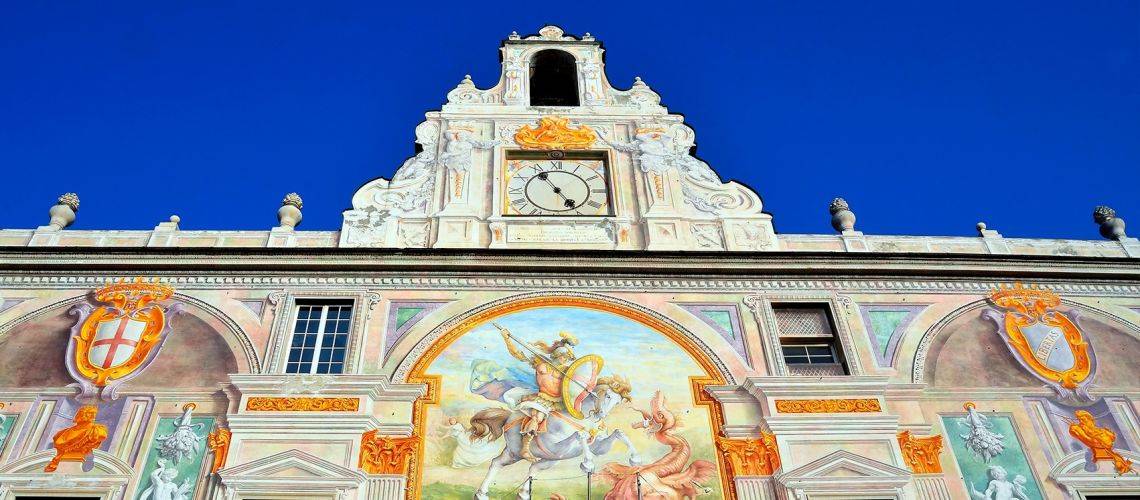

Life in Genoa goes on. Work on an important new road is now done on three shifts, around the clock; due for completion next April, it is expected to be functional by November. Genoa's famous International boat show, the Salone Nautico, with more than 1,000 boats on view, goes forward as planned from September 20 through 25. At Palazzo Ducale, the center of culture in a deeply cultured city, an exhibition devoted to the great Genovese violinist Nicolò Paganini, born in 1782 begins in October. "This will be an extraordinary occasion for people to know the city, to appreciate an event that involves top contemporary artists, beginning with Ivano Foassati, its curator," says Palazzo Ducale president, the Genoa-born actor Luca Bizzarri.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.