Back to School Time for Italian Youngsters

ROME - Schools are about to reopen for Italy's students, although not without problems. One of these has been the disaster earthquakes wrought to school buildings. The good news is that in quake-stricken Sarnano at Macerata, a town severely damaged by a quake in 2016, a new school, constructed with anti-seismic technology, will open on time. The Giacomo Leopardi middle school, with facilities for sports and the arts as well as classrooms, was built in just five months thanks to private funding from two foundations: Diesel founder ("the jeans genius," he is called) Renzo Rosso's Only the Brave and the Andrea Bocelli Foundation. Bocelli, whose foundation invites contributions from donors, sang the Italian national hymn at the inauguration of the school last May. Among those also on hand: the popular Renato Zero. (See >>)

In the village of Grottamare in the Marches, the school cannot open because its roof is at risk and the contract for its reconstruction turned into a bureaucratic battle. Children from nine classes will study in improvised classrooms in the town hall and in its library. This brings a personal memory. When my daughter attended a middle school in downtown Rome in the 1980s, a stone's throw from Parliament, the teachers warned students to walk close to the wall because the winding staircase was insecure (!) When I suggested to the principal that I would lodge a formal complaint, she asked me to desist, for, "To repair it would mean shutting down the whole school for a year."

Schools reopen on different dates, depending upon the region and presumably the climate. Bolzano's schools in the mountainous Alto Adige were first, opening Sept. 5. Schools in Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Piedmont opened Sept. 10, followed by Lombardy and Umbria Sept. 12. A host of others open only Sept. 17, with the very last in Puglia Sept. 20.

For the schools everywhere, a serious problem, say many school principals, is a lack of teachers, which suggests that the cause is a lack of government funding. In Pavia the local press reports that the middle schools there would require 152 more teachers, and the high schools, 116. In Parma the teachers branch of the CISL trade union reported in August that a stunning 1,103 more teachers should be hired. The vacancies, said a CISL spokesperson, are due to retirements and transfers.

For the very youngest students, a problem is vaccinations. A campaign against vaccinations, which may have been at least partly manipulated, means that many parents refuse to have their youngest children vaccinated. After a nationwide debate with countless educators protesting that unvaccinated children would endanger the others, Education Minister Marco Bussetti offered an ambiguous way out, saying on Aug. 30 that school principals can accept children whose parents present a self-certificate that they have been vaccinated. "The law says clearly that children in class who bring a self-certification signed by their parents can be accepted," he said. Should things go wrong, the principals would have no responsibility since, "That responsibility lies with the parents," he declared. A goodly number of principals throughout Italy reject this, saying they require children to be vacciated.

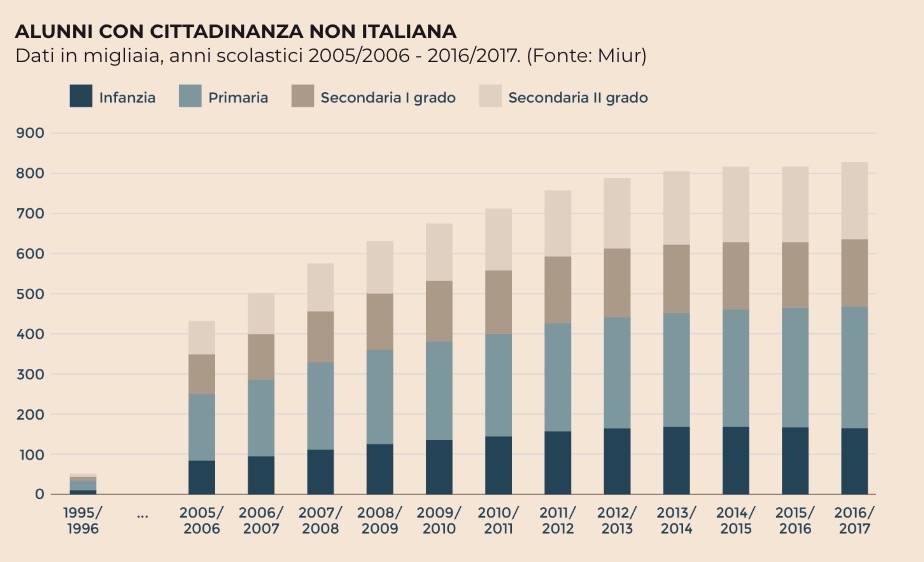

The children of immigrants are also changing today's Italian schools. Some 826,000 students -- 9.4% of the total -- have non-Italian citizenship, or 11,000 more than in 2017. Almost two-thirds were born in Italy and are hence second generation immigrants. More are boys (52%) than girls (48%). The largest proportion have Rumanian parents (19%) following by Albanians (under 14%) and Moroccans (12%). Other countries represented in the classroom are China, Pakistan, Egypt, India, Philippines, Moldavia. Almost all complete secondary school studies. The good news is that, of these, over one-third continue with university studies, aiming particularly toward a degree in social studies.

One of the most intractable problems is the ever younger age of those trying out drugs. Today the age for a first use of a drug has dropped for boys to 13 and for girls, to 15. In an attempt to deal with this the Interior Ministry is hiring anti-drug police to serve as lookouts near schools, offering them short-term contracts at a total cost of $800 million.

Another working to combat school children using drugs is Mauro Ioacoppini, 56, a consultant in legal medicine at Rome's "La Sapienza" University. Ioacoppini has developed workshops -- he calls them "laboratories against drugs" -- which he takes into schools. "The school is fundamental for prevention and to explain about the dangers," he said in an interview in La Repubblica daily. Do the students pay attention? "I have the sensation quite often that they just refuse [the concept] or are indifferent or even take it as a challenge." But not everywhere, he went on to say, particularly in areas where families have already witnessed a relative or friend with a drug problem.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.