1938: Diversi Premiers in the US on International Holocaust Remembrance Day

Eighty years after the fascist regime’s promulgation of racial laws, the film sets out to examine through the voices of witnesses and historians what the implementation of these laws meant for Italian Jews and how the population, both Jewish and non-Jewish, reacted to one of the most tragic examples of racial persecution in human history.

Most importantly, director Giorgio Treves unearths Italy’s culpability in the persecution like a stubborn weed, and reminds us of the need for education and reconciliation in order to point out intolerance and injustice in the future, and develop institutions that protect human rights against prejudice. Otherwise, as philosopher George Santayana wrote, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Touching upon International Holocaust Remembrance Day, and 1938: Diversi, the Ambassador called it “a vivid and painful reminder” of the “blinding darkness of stereotypes ready to strike. When social discrimination and violence emerge, we must be ready to act swiftly to avoid these threats. As a European, I have a special responsibility to this.”

Although Italy is, and should be, “proud of our history, we need to be engaged now. We are the heir of a great past, but we have a responsibility to pass on to future generations what we have to do, and keep history books open on their shelves.”

After the Ambassador’s powerful words, and the screening of the documentary, Treves quietly took his place on the small stage. He was accompanied by Dr. Elizabeth White and Lindsay Zarwell, Senior Historian and Film Archivist at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, respectively.

Moderated by Susan Barocas, former Director of the Jewish Film Festival in Washington, DC, the conversation revealed how the film stemmed from a deep need to understand the truth of the past in the context of personal stories. For Treves, premiering 1938: Diversi in the United States helped him travel “back to the past of my family, and things left unsaid.” In 1940, his parents fled Turin and the fascist racial laws on the last ship to sail for America, the George Washington.

“This is where I was born, and where we were welcomed as refugees,” Treves shared. His cousin, who just turned 90 a few weeks ago, was one of the witnesses included in the documentary.

“I wanted each witness to speak about a different angle, and he represented those who did leave the country.”

However, the film does not begin its story with the rise of antisemitism in Italy. Instead, cartoons, comic strips, and short films of the Italian-Ethiopian war in 1935 illuminate the decisive role played by the media in promoting racism, and establishing dangerous stereotypes. The seeds of hatred for the “other,” or diversi, were planted, along with a nationalism that supported the idea of the so-called “Aryan race.” The archival footage also reveals a part of Italian history that is not well-known abroad, and needed to be examined more deeply.

In a country that had not traditionally been anti-Semitic, fascist propaganda promoted in movies, songs, and even children’s books came as a shock to the Jewish population. In the early 1930s, many prominent politicians, leading businessmen, and successful doctors were Jewish. But the fascist media and propaganda had created a new Italy controlled by fear and insecurity, still suffering from the trauma of World War I.

Treves was able to capture this transformation in old footage from the Istituto Luce, a propoganda machine originally created by Benito Mussolini in 1924 to create racist messaging for movies. Frantic black and white images of soldiers moving in sync in fascist uniforms through Piazza San Marco made the American audience uncomfortable; stern gray jackets, boots, and men amid the sun-soaked, jovial colors of Venice we are all familiar with was an ugly awakening to Italy’s role in World War II.

The director wanted to use archival footage, voices of witnesses, and actors to read the words of Mussolini to make the perspectives in the documentary “pure.”

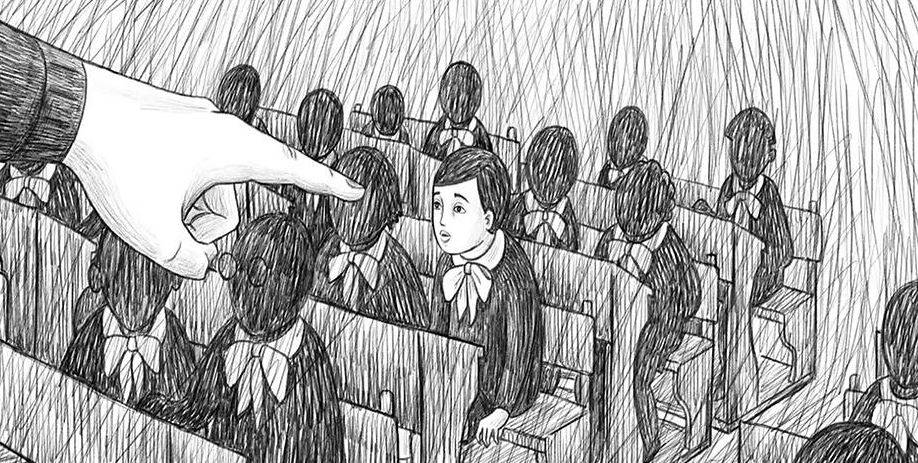

“Their voices couldn’t be manipulated. If actors read the lines of Mussolini, they couldn’t be manipulated by the personal charisma of the person reading them,” Treves said. Reconstructions of discrimination and humiliation in animated sequences also keep the audience engaged throughout the documentary, with the voices of witnesses narrating over images of their past.

“The animations do a remarkable job of driving the point of the documentary and capturing visually the stories the witnesses shared,” Zarwell noted.

“The story of the boy banned from school is nothing without the historical context, but at the same time, you can’t understand historical context without looking at the perspective of the people involved,” Dr. White added.

“Who and what was lost, ‘choice-less choices’, and harassment are better understood through stories, and their stories continue to motive me in my work at the Holocaust Memorial Museum.”

“The movie is not an answer, but it is a reflection of what happened, so we can avoid falling into a similar place,” Treves stated at the end of the discussion. “Students are my audience – I want them thinking critically about what is going on in the world right now. Each one of us has to determine how we behave now, based on what we know from history.”

1938: Diversi ends with a famous quote from Umberto Eco: “We must keep alert, so that the sense of these words will not be forgotten again. Fascism can come back under the most innocent of disguises. Our duty is to uncover it and to point our finger at every one of its new instances – every day, in every part of the world. Freedom and liberation are an unending task.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.