Evelina Meghnagi: the Melodies and Journeys of Sephardic Jews

Nowadays it’s kind of funny how we literally carry music around. In our I-pods and Mp3 players there can be thousands of songs and we bring them from a place to the other. Music has always been carried around, though, in a more metaphorical sense.

Songs are something that trace as far back as pre-historical time. It’s hard to say why people sing or when they started, why people put together certain sounds, tones and vocal utterances to form a melody. Who was the first man who decided to beat two stones together and how did he come up with a certain rhythm? Entire cultures, religious ideas begin with dancing and singing. This is what is fascinating.

It’s easy to see how a song can be created rationally for a ritual, how a prayer can be put to music, but often what happens is the other way around. It’s the spontaneous magic of a tribal dance that built a ritual, the “mystical” effect of certain natural sounds or patterns of rhythm that through time and rational progress, established a tradition. Music is part of culture and religion but it’s beyond entertainment, beyond religion, beyond a sense of something fun and communal: it’s irrational and it’s a natural instinct that has a powerful and deeper effect on us. And it’s the catharsis that music creates which allows for a strange state of trance, you could call spiritual or simply human, although the name doesn’t matter that much...

Going back on how music was taken from place to place thousands of years ago, we know of nomads, shepherds, traveling storytellers, tribal shamans, little villages moved around the Mediterranean and the surface of the Earth bringing with them not only objects and belongings, but also songs.

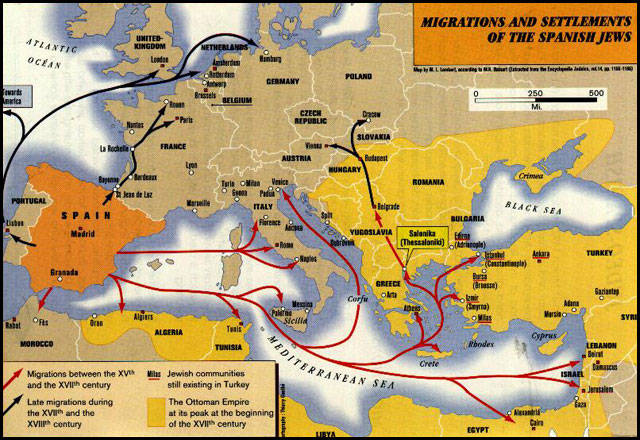

Eternal voyagers, among various nomadic tribes, are of course the Jews, who went from a nomadic tradition to a fate of continuous “diasporas”, exiled from Egypt, separated again after the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed, kicked out of Spain in the 15th century, dispersed all over the Middle-East and North Africa, persecuted all over Europe and forced to leave newly found “promised land” in Lybia, Lebanon and Yemen from where, in some cases, even recently they had to flee again.

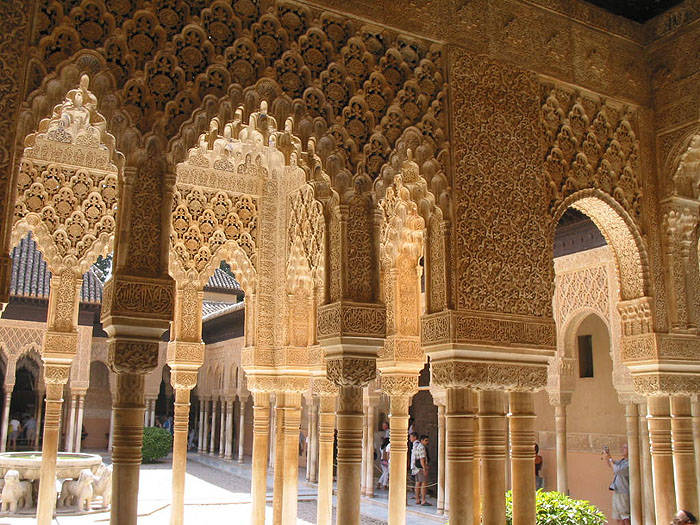

The Jews who moved around the Mediterranean and the Middle-East or those who were first born in Spain are usually called Sephardic. This term can have an ethnic connotation but also a religious one. The Sephardic rituals are slightly different from modern “mainstream” Judaism or for example from the Chasidic Jews, from the eastern European Ashkenazi context or the Yiddish one. Although ideally Judaism doesn’t allow mixed marriages, it’s impossible not to notice how Sephardics are ethnically and culturally mixed with Arabs, Turks, Africans, Persians both in the physical traits and the traditions, the food, the clothes and sometimes even the language (many dialects that mix Hebrew and Arabic). In most cases it was a clash of cultures but sometimes - like in Spain during the time of Avverroes, Maimonides in the 13th and 14th century- it was a peaceful intellectual debate, a cohabitation of communities; something as elaborate, mystical and fascinating as the Alahambra in Granada, a testimony of Arab culture but also of many Jewish roots and ideas.

On a rainy night in New York City, on April 26 2010, as part of the festival Divinamente New York, the Italian Cultural Institute hosted an event that for a couple of hours immersed its audience in the smell of spices, the heat of the desert, the colors of far away lands, the taste of honey-filled sweet dishes, fruit and the magic of storytelling through music.

Sephardic music was born in medieval Spain, with canciones being performed at the royal courts. It developed mixing melodies and sounds from Morocco, Turkey, Greece, Italy, the Balkans and what was once the Ottoman Empire.

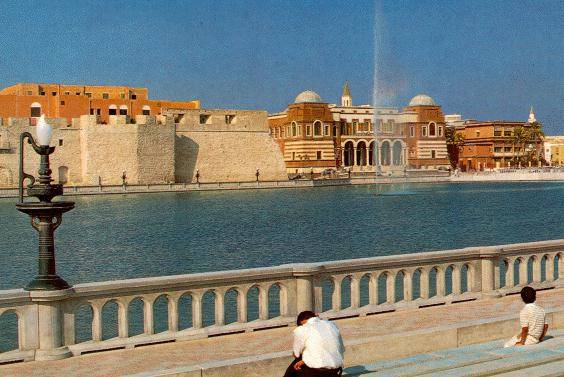

Evelina Meghnagi held a concert in which all these traditions came together, combined with her personal history, a Jew who was born in Lybia and left to live in Rome after 1967 and the political consequences of the 6 day war in Israel.

Sephardic songs have a lot in common with Arabic poetry. If anyone is familiar with Khalil Gibran, his themes, ideas and poems, they can have a pretty basic idea of what this poetry represents: something in between popular beliefs, a “neo-platonic” idea of love - represented both by love seen as a constant longing, as a sickness and at the same time filled with eroticism and graphic images like in the Song of the Songs- and alchemy, mysticism and philosophy.

Usually these sung poems have certain canons: there are ceremonial poems - because weddings, births and other steps of the life-cycle are essentially linked to music - there are romance songs and topical or "dancing" songs.

In the show “From Voice to Voice” (di Voice in Voce) which Evelina Meghnagi has performed in various countries, she leads the audience in a beautiful journey from one song to another, from place to place. Before every songs she recited a poem, a psalm, a quote from the Song of the Songs, a personal story or just shared her humor and her warm smile. Evelina Meghnagi is a performer, an actress and a singer and her presence is itself theatrical. A loving and inspired gaze, a matronal figure, a gorgeous yellow-golden tunic with a red "cape" and a silver necklace, a loud voice through which she provided a context for her stories, talking in English, slightly tinged with a Roman accent.

The two musicians accompanying her, Domenico Ascione and Arnaldo Vacca (Ashira Ensemble), a guitarist and a percussionist, delivered an exciting performance. Going around with our I-pod in our ears sometimes we forget the power of live music, of being part of an audience sharing a common physical experience. In this context the heartbeat starts following the drums, the breath is regulated by the voice of the singer and the guitar's arpeggios hit strings within us that raise a strange unconscious awareness.

The experience becomes very visceral. This kind of music is often meant for dancing, either in circles (hora) or for belly-dancing or, in some cases, twirling around like dervishes, losing the perception of the outside world. In all of these cases it is a music with few intellectual filters, it speaks to our basic instincts.

Evelina Meghnagi managed to keep her audience under a spell, while singing songs from different cultures within the Jewish world, either from Northern Italy, Spain, or Lybia.

The Italian Cultural Institute was packed with members of the Yemenite and Sephardic communities, Italians, Jews and New Yorkers of all faiths. The director of Centro Primo Levi

Natalia Indrimi was present and enjoyed the performance. The show is also meant to make the voice heard of certain communities that are less "famous" than others throughout Jewish history. In particular Evelina Meghnagi who was born in Tripoli and now lives in Rome speaks on behalf of a community who lived a somewhat "hidden exodus" in the 1960s and that had to restart a new life from scratch assimilating into the already well established Roman community. That particular community grew up with these songs as daily tunes and lullabies.

Evelina Meghnagi sang various ballads that because of their similarity of rhythm and tone, reminded in fact of lullabies, something that we don't understand completely but that act at a deeper level, calming and soothing, cradling us.

If you've ever been in the desert (in the Middle-East or North Africa) you might experience a strange feeling when you leave it. In Italian it's called "mal d'Africa" and is quite unexplainable, because it's beyond one's faith and family history: sometimes it just happens. Having traveled a lot in that area, sitting in Beduoin tents drinking tea while listening to that same music, having absorbed stories from family friends that carried those traditions made this experience even more meaningful for me but it was a show that spoke to a general audience as well.

Overall, what Divinamente New York is about and what this event portrayed really well was that sense that, whether you are a believer or not, sometimes religious traditions can be very powerful and culturally significant on various levels. Religion, much like philosophy, is born with awe, with amazement, with the acknowledgment of the power of life and in the deepest Jewish (but also Arab) tradition, songs, dances and the power of life are one and the same.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.