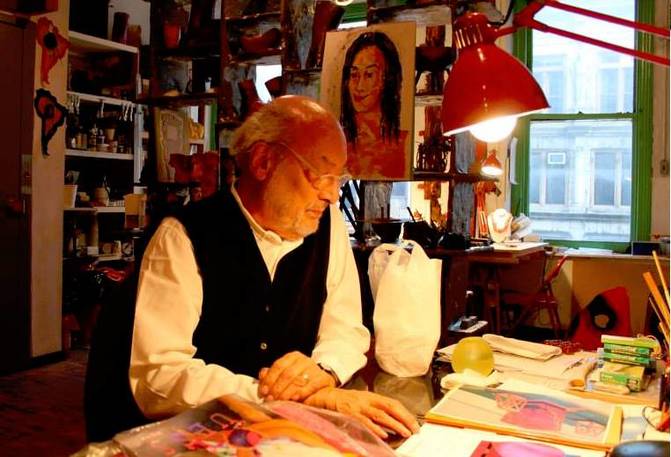

Gaetano Pesce is an artist whose political stances have long kept him one step ahead of his time. Today he is an icon of the creative avant-garde, known around the world for the close link between his Italian background and his self- expression. Never one to hold his tongue, he frequently causes stirs in the art market. Design is also an exploration of existential problems;

Pesce [2] has expressed such concerns without hiding his disappointment in the Bel Paese, as in his famous Italy on the Cross. For Pesce, art and design means engagement, means casting one’s lot with the people. In his work he strives to combine practical demands with a philosophical, political or existential message. That is how design acquires cultural relevance: “When instead of simply creating a practical object, something to sit on or eat with, we succeed in making people think,” says Pesce. “Ultimately that’s the role of art.”

You are a major figure in Italian design, particularly “radical design.” Do you like that description? You’re known as being a great provocateur.

I can’t be the one to answer that. That’s up to the public to whom my work is dedicated. If being radical means looking ahead and experimenting, then that’s me. As for being a provocateur, I don’t do it on principle; provocation implies novelty, invention and discovery, and sometimes I’ve happened to embody that.

In 1972 you participated in a famous exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape [3].” On that occasion, the slogan Made in Italy was coined, a symbol of exceptional quality. Can you tell us about that exhibit and what it has meant for you, for Italian design, and for the image of Italy in the United States?

That exhibit was extremely important in establishing Italy’s landmark contribution to the history of design. Looking back 44 years later, Italian design remains the most important, on account of its creative talent, sure, but more importantly its industries.

For me, that exhibit was the start of a way of considering design as a comment on reality; in my opinion, that’s what it continues to be, and it will be more and more. In other words, design as art. I always thought design would become the art of the future, which isn’t a given yet but people talk that way more and more. I thought so at the end of the ‘60s and I believe so today. The situation of design is to usher in a far vaster culture.

How is Italian design perceived outside our country, particularly in the US? Do you think we still have something to “teach” the world?

Design in the United States

isn’t design; it’s redesign, a reiteration of something already seen or a product derived from marketing. I’m convinced that Italy, on the other hand, has long been the country that comes closest to manifesting innovative design.

Since 1983 you have been in New York regularly. You live here, work here, and have completed many projects that by now have become part of the city and its Italian spirit, from architecture to collectibles to furniture. Some of your work is on display in the city’s major museums, including MoMA and the Met. Is there a work of yours here you like most? One we might point out to our readers?

There are two. One finished, the other not. The first is 1981’s New York Sunset, a sofa that speaks to the identity of a city that’s probably in decline. The other is a project I made after 2001, when the Twin Towers were destroyed by those imbeciles. My idea was to respond to the pessimism of terrorism with an image of optimism, a positive outlook using the “I Love New York” logo, an image beloved by the whole world.

Architecture is another passion of yours. How did you come up with the idea for the Porta Molino tower in Padua? Your proposal for the project sought to use art to pay tribute to a place. Can you tell us what happened? What’s going on with the project?

I attended high school in Padua, so I have long been familiar with that tower where Galileo worked out his theories and discoveries. For a long time I wondered why Padua hadn’t celebrated Galileo in such a way as to attract visitors and let the world know that this great genius of ours had spent an important part of his life there. More recently I tackled the problem by dedicating more time to a project called “Padua Honors Galileo,” to pay tribute to the place where he made his discoveries. I’ll be presenting the town council with the results of that work soon.

I hope they’ll accept it, so that there will be a new attraction, among the many extraordinary jewels Padua already has, first and foremost the Scrovegni Chapel [4]. I’d also add that in the past, Italy carried out projects that were copied throughout the world for their innovative power. Look at Brunelleschi [5]’s dome. Palladio [6]’s classicism. I wonder why that doesn’t happen more in our country, why the building projects fall under the category of construction rather than architecture.

What would you say to a young person hoping to embark on a career like yours?

Be curious not conservative.

Too see one of our interviews with Gaetano Pesce: >>> [7]

Source URL: http://ftp.iitaly.org/magazine/focus/art-culture/article/tool-social-criticism

Links

[1] http://ftp.iitaly.org/files/gaetanopesceiitaly1463152121jpg

[2] http://www.gaetanopesce.com/

[3] http://grahamfoundation.org/public_exhibitions/5040-environments-and-counter-environments-italy-the-new-domestic-landscape-moma-1972

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrovegni_Chapel

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filippo_Brunelleschi

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_Palladio

[7] https://youtu.be/_nD4rXyYFUI