When in 1939 Pope Pius XII granted Italy two Patron Saints—Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Catherine of Siena—he solemnly declared that St. Francis was “the most Italian of all saints and the saintliest of all Italians.

Whereas the second part of that statement is pretty obvious, despite fierce competition in theland “of poets, saints and navigators,” the second part always made me think about what made him characteristically Italian. What was it? His deep humanity, his cheerfulness, his love of nature, his untiring desire for peace? These are all beautiful traits of his personality, but the Italians hardly have a monopoly on them.

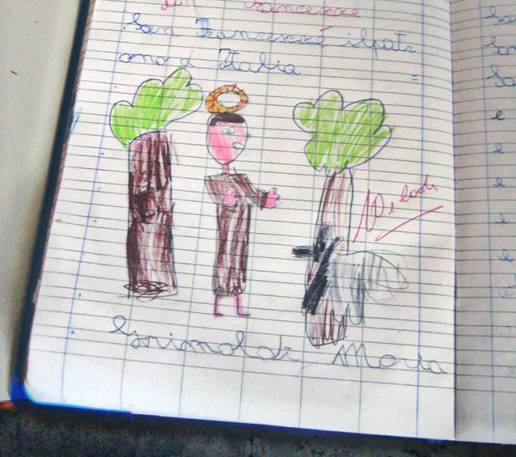

The most Italian of all saints

As I discovered in my second year of high school, what makes him so Italian is that he is the author of the first poem in the Italian language: The Canticle of Creatures. And for a nation that for about six centuries was only unified by its literature, being the founder of its poetic tradition is quite a big deal. I recognized the canticle from the modernized versions they had us sing in church as children, but the original was a different story. I could understand almost every word, but it was not the language I spoke with my friends or even in school. It had the arcane beauty of sounds and expressions that partly disappeared with time and partly typified the Umbrian vernacular that Francis spoke.

A solemn, yet joyful book of prayers

The canticle is a poem and a prayer (for some critics a prayer doesn’t count as a poem, but that escapes my understanding), a solemn yet joyful prayer of praise to God, the Creator for and from all creatures. Creatures that Francis calls, with moving confidence, ‘brother’ and ‘sister,’ as if he were extending Christ’s message of brotherly love outside its human boundaries. Each creature is defined with a perfectly equal number of adjectives (four adjectives each for the four fundamental elements, etc.) that aim to recreate in the poem the sublime harmony of creation. And each adjective is simple yet fitting: (Brother Sun is “beautiful and playful and robust and strong”(bello et iocundo et robustoso et forte). Sister water is “very useful and humble and precious and chaste” (multo utile et humile et pretiosa et casta). Wouldn’t you feel silly adding a single adjective to Francis’ description?

Francis’ multifaceted legacy

Francis even goes so far as to call death his sister. He probably felt its presence keenly while writing the canticle. He was likely quite sick at the time, weakened by fasting and penitence, and only a couple of years away from dying. But, as we know, death would not stop Francis’ brave and revolutionary march; his legacy is alive and well, despite the quarrels among his closest followers that led them to splinter off into dozens of different orders and congregations.

I see Francis’ presence in the environmentalist movement. I see his signature in every honest and courageous negotiation for peace. I see his style in every effort to bring people of different religions to a frank and open dialogue. And of course I contemplate much of Francis’ teaching in the words and actions of the first Pope who took his name.

But I like to think first and foremost that the Italian language is also one of his most precious legacies, a language that has his seal of approval and his blessing. He was our first poet, one of the founding fathers of our literary language, and every Italian poets and writer who has come after him is in his debt. Even the lofty, the aristocratic and the atheistic follow in the literary footsteps of the poor beggar from Assisi.

Source URL: http://ftp.iitaly.org/magazine/focus/art-culture/article/friar-francis-founder-italian-literary-tradition

Links

[1] http://ftp.iitaly.org/files/sanfrancesco1416973170jpg