Little excites more savage controversy than debates over the behavior and policies of the Roman Catholic Church in the time of Italian Fascism. The record is ambiguous. John Cornwell’s Hitler’s Pope, published in 1999, based on privileged access to Vatican secret archives, was accusatory and persuasive, but five years and a flood of diatribes later the judicious Cornwell somewhat modified his criticism of Eugenio Pacelli, who became Pope Pius XII in 1939. In an interview with the Economist Dec. 9, 2004, Cornwell said, “I would now argue, in the light of the debates and evidence following Hitler's Pope, that Pius XII had so little scope of action that it is impossible to judge the motives for his silence during the war, while Rome was under the heel of Mussolini and later occupied by Germany.”

Certainly Vatican policies toward Fascism appear less than clear. Pius XII did not intervene to stop Roman Jews from being deported to concentration camps, even as some Jews were being given refuge in Catholic institutions. Another example: following an appeal by a Jewish rabbi, a bishop near Pisa received authorization from Rome to help Jewish families escape capture and deportation; local nuns who normally printed prayer cards were drafted into printing forged documents for endangered Jews.

But what was the view on high? To what extent had the signing of the Concordat in 1929, which gave priests salaries in schools and the Vatican formal recognition for the first time since unification of Italy, driven Vatican policies, and Pius XI, into the arms of the Duce? Did the experience of young Pacelli, during his decade as a young Vatican diplomat in Germany observing the rise of Hitler, make him subsequently soft on the Nazis and tolerant of Italian Fascism as well? Given Vatican secrecy, how would one know?

Hence the welcome new access to archival documents of the Vatican, made available over the past year to researchers. Some of the new research delves as far back into the past as the Inquisition, the subject of a conference held in Rome in February under the auspices of the Accademia dei Lincei. Another of those taking benefit of the new access is historian Lucia Ceci, whose work sheds revealing light on the secret debates within the Vatican over its dealings with the Duce. The author of Il vessillo e la croce, Colonialismo, missioni cattoliche e Islam in Somalia (1903-1924), published by Carocci in 2007, Ceci is a researcher in contemporary history in the Department of Letters and Philosophy at the Tor Vergata Rome University. She has published scholarly articles on, inter alia, Liberation theology and politics in Latin America.

Previews of her latest research on the Church and Fascism, to be published in the forthcoming issue of Rivista Storica Italiana, have already surfaced in Corriere della Sera in an article by Antonio Carioti on Oct. 23, 2007, and in Emma Fattorini’s Mar. 9, 2008, article in Il Sole-24 Ore, headed, “Pius XI’s failed attempt to stop the war in Ethiopia”, with the subhead, “New documents prove that the Holy See opposed the aggression, but decided not to intervene.”

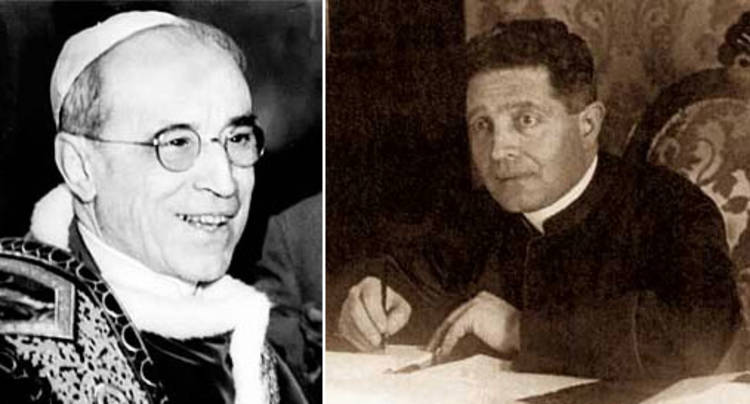

Among Ceci’s key sources are hand-written notes of private meetings between Pius XI (Achille Ratti) and a former deputy chief of Azione Cattolica, Mons. Domenico Tardini (1888-1961, who had been serving as Undersecretary for Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs since June 1929. The autumn of 1935 found Italy on the verge of invading Ethiopia. Tardini was disgusted: a note found by Ceci shows the following list (my translation, with an uncertainty or two indicated), in Tardini concludes by accusing the Duce of being “divinized” like an ancient emperor:

“Fascism has created confusion between the party, Italy and the Duce. Conclusion: a whim of the Duce is Italy’s ruin.

“It has destroyed all freedom of action and discussion. Conclusion: the Italians are now a people of sheep, who run where the shepherd herds them with his stick.

“It has educated generations into violence. Conclusion: everyone is a hero, ready to use his fists, certain that the others will be left only with…taking punches

“It has followed foreign policies of improvised body blows (colpi di testa), rudeness, threats, blows. Conclusion: turned the entire world against Fascism.

“It has forecast, premeditated and proclaimed an empire. Conclusion: it is conducting a harsh and costly colonial war, with just two aims: to waste money and to conquer inhospitable lands.

“It has cried to the four winds the strength, the grandeur of Italy. Conclusion: today we are a people of beggars who put on airs...as per Sardanapalos [Ed.: Legendary warrior king in Mesopotamia], a feeble and backward people who act as if they were the greatest on earth.

“It has divinized the Duce, making everyone bow before this god [Nume]. Conclusion: political life no longer exists, nor the possibility to forge new energies for the inevitable needs of tomorrow.”

--Note of Dec. 1, 1935, first published in Il Sole-24 Ore, Mar. 9, 2008

Ten weeks before writing the above, this seriously anti-Fascist high official of the Vatican and papal confidant had hoped that the Vatican would halt the Italian invasion of Ethiopia. Triggering the discussion was a speech the pope made in August to a group of Catholic nuns, in which he declared that “a war of conquest” would be “unjust.” International press agencies quoted his words, and the Italian Foreign Office—presumably Count Ciano himself—reacted bitterly. The Vatican backed off, with Osservatore Romano publishing a softened account. It happened that the Vatican’s foreign affairs minister, the future pope Pacelli, was away on vacation, and so Monsignor Tardini was tending foreign affairs in his place. Tardini obviously agreed with the original version, for he personally drafted two slightly differing letters opposing war and then offered them to the pope for approval. Both drafts, as discovered by Ceci and published by Corriere della Sera, show strong Vatican disapproval of the invasion, but with differing justifications:

Draft letter 1: “ We ardently desire and with all our soul hope that Your Eminence [i.e., Mussolini]…will be able to reach the legitimately sought goals on the way toward justice and peace. That if to that most noble aim, it be necessary to sacrifice some understandable desire for more abundant and immediate successes, it would always be, for Your Eminence, not the last demonstration of true grandeur to have spared the Italian people the ruination, the pain, the mourning, that are inseparable from every war. and that are today all the more serious and greater for the tremendous power of the tools of death.”

Draft letter 2: “We wish to think that it is not completely impossible that, through the authoritative intervention of some friendly power, and with the consensus of Abyssinia, one could give Italy, in that territory outside Italy’s own borders, an area established in such a way as not only to extend the said borders, but to make them more definite and secure. That if this should happen, the sense of moderation and desire for peace of which Italy would give evidence would be greatly appreciated throughout the world, and Italy itself could in future find in Abyssinia, as we fervently hope, a sure and grateful friend, rather than a hopelessly angered enemy [insanabilmente irritato].

In Draft 1 then proposes that the Duce will show “true grandeur” in the long run by sparing the Italians from war; in Draft 2, the appeal is to seek a rapprochement with Ethiopia that will bring worldwide approval of Italy.

By September 20 the Vatican’s official Secretary of State, Pacelli, was back from his month-long vacation and met with Pius XI. On the agenda were the draft letters plus a letter the pontiff had received from the Archbishop of Westminster and Catholic primate of England Hinsley, asking the pope to intervene to halt war. Pacelli’s own notes reveal that the discussion centered not on lofty principles, but on the difficult logistics of invasion of Ethiopia, with its warring tribesmen, and on the negative consequences to Italy’s image if it were the aggressor.

In the end, political pragmatism won the day: The risk, as both Pacelli and pope agreed, was that the Vatican might end up as mediator, overly involved in a pan-European conflict in which the League of Nations also played a part. A disappointed Tardini confided to his diary that, “At the end of the day the Holy Father decides not to send any letter for now.”

There was one last effort. On Sept. 29, just a week later, Jesuit priest Pietro Tacchi Venturi called on Mussolini to urge him if possible to avoid war “so as not to put Italy into a state of mortal sin.” Unmoved, the Duce replied that the democracies were determined to “inflict a mortal blow against fascism.”

The invasion took place; Italian gunners fired upon sword-carrying Ethiopians on horseback; and on Dec. 3, 1935, Mons. Tardini wrote, in another note turned up by Lucia Ceci: “The ambition of one man is digging the grave for all of Italy.”

Tardini was elevated to cardinal in 1958, the year of the election of Pope John XIII. Tardini then served as Secretary of State for the Vatican in 1958 until his death in 1961. Tardini is buried in Vetralla, near Viterbo.

As an historical footnote, the late Pope John Paul opposed President George W. Bush’s decision to go to war in Iraq. On Ash Wednesday in 2003 the pope’s former nuncio (ambassador) to the United States Cardinal Pio Laghi called on President Bush in Washington in a last-ditch effort to convince the President that the invasion of Iraq would be a fearful mistake. George Bush accepted the visitor, but not the advice.

For an abridged version of Cornwell’s book, see: http://emperors-clothes.com/vatican/hitlers.htm [2]

Source URL: http://ftp.iitaly.org/magazine/focus/facts-stories/article/out-archives-vatican-doubts-over-duce

Links

[1] http://ftp.iitaly.org/files/1429harrisvatican1205423170jpg

[2] http://emperors-clothes.com/vatican/hitlers.htm